The Fluctuating Fortunes of Wildlife

In this report we review the counts of large herbivores in and around Amboseli National Park since the 2009 drought and consider some ecological and social consequences.

The fluctuating fortunes of wildlife, predators, and pastoralists in Amboseli.

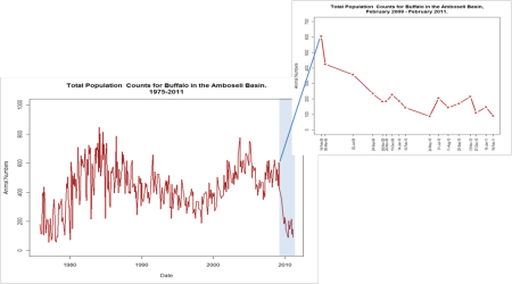

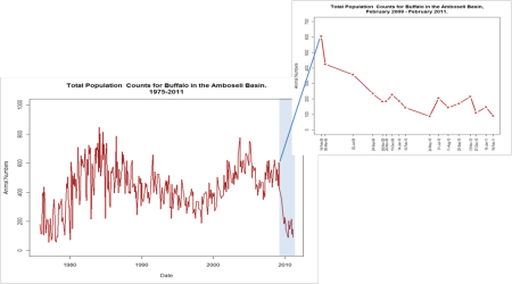

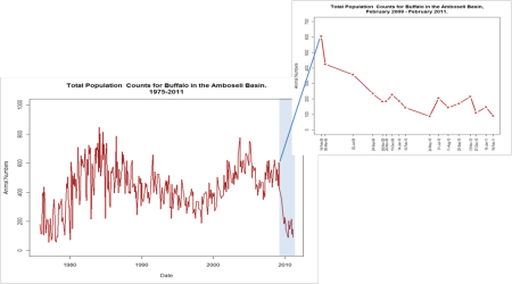

The sample ground counts and total aerial counts (Fig. 1 and Fig 2) show the heavy drought losses wildebeest, zebra and buffalo, the main prey species of Amboseli’s large carnivores, suffered in the last four months of 2009 drought. The remaining herds moved out with the rains of December 2009, leaving a few dozen animals in the park. In the following dry season we had expected only the remnant herds surviving the drought to return to Amboseli. Quite unexpectedly, the remnant herds were accompanied by an influx of over 1,400 wildebeest and several hundred zebra from adjacent populations, most likely Tsavo and northern Tanzania. The herbivore populations built up to a peak of some 1,500 wildebeest and 2,500 zebra in the late dry season of 2010. During the November-December rains the numbers fell sharply again with the migrations. The migrants were expected back at the beginning of the dry season in January of 2011, but unexpected cyclone rains fell across the region and kept them out of the park in the wet season dispersal areas.

The sample ground counts and total aerial counts (Fig. 1 and Fig 2) show the heavy drought losses wildebeest, zebra and buffalo, the main prey species of Amboseli’s large carnivores, suffered in the last four months of 2009 drought. The remaining herds moved out with the rains of December 2009, leaving a few dozen animals in the park. In the following dry season we had expected only the remnant herds surviving the drought to return to Amboseli. Quite unexpectedly, the remnant herds were accompanied by an influx of over 1,400 wildebeest and several hundred zebra from adjacent populations, most likely Tsavo and northern Tanzania. The herbivore populations built up to a peak of some 1,500 wildebeest and 2,500 zebra in the late dry season of 2010. During the November-December rains the numbers fell sharply again with the migrations. The migrants were expected back at the beginning of the dry season in January of 2011, but unexpected cyclone rains fell across the region and kept them out of the park in the wet season dispersal areas.

The February total aerial count of the park gave the lowest wildlife numbers recorded in 43 years of ACP surveys. Wildebeest numbers dropped to 10 and zebra 71. Buffalo numbers dropped from over 200 to 90, meaning that more than half the population moved out of the basin with the unseasonal rains. Such an outward migration of buffalo from the park has not been recorded since the late 1960s and early 1970s. The March count showed little increase in herbivore numbers. The low counts mean that Amboseli is sure to skip the January to March dry season and that the migrations will extend from November until the end of the long rains in May or June. The long absence of wild herbivores will confront lions and hyenas with extreme food deprivation and raise the specter of conflict with livestock once more.

The extreme fluctuations in prey species in Amboseli since 2009, coupled with the longer term changes since the early 1990s, largely explains the growing conflict between large carnivores and Maasai herders around the park, as detailed in earlier reports.

The precipitous drop in lion and hyena prey species in the Amboseli Basin since 2009 explains the sharp increase in carnivore-human conflict since the 2009 drought, as predicted at the Emergency Drought Workshop of December 2009. Carnivore attacks on livestock began immediately after the drought, coinciding with the wildebeest and zebra migrations and the return of the Maasai with their remnant cattle herds. At that stage, nearly all attacks on livestock were by lions unable to find wild prey in the vicinity. Contrary to expectations, hyenas did not attack livestock. They were getting by on the 10,000 or so carcasses left by the drought.

The return of the migrant herds in the dry season of 2010, accompanied by an influx of animals from Tsavo and Tanzania, gave the carnivores enough to feed on without killing livestock. The drop in zebra and wildebeest numbers with the October rains of 2009 led to a further round of livestock attacks, this time with hyenas joining lions after they ran out of drought carcasses. A total of 274 livestock were killed by predators in September and October 2009. Hyenas killed 103 animals and lions 57. The unseasonal rains in February kept the migrant herds out of Amboseli, resulting in a continuation of carnivore attacks on livestock when they would otherwise have dropped off with the return of the migrants.

The rising conflict between large carnivores and people in Amboseli is explained in large part by the collapse of their prey base in the 2009 drought. When the prey-based dropped by three quarters in a matter of months, the lion and hyena population would have dropped sharply in the following year was it not for the lion attacks on livestock and hyena dependence on drought carcasses. As it is, the lion population has fallen by nearly a half due to reprisal killing by herders. But several other ecological and social changes over the last two decades and more contribute to the ecological and social fallout of the 2009 drought.

The most important factor explaining the rising attacks on livestock during the rains is permanent settlement. Until the early 1990s, Maasai pastoralists moved their livestock in tandem with the wildlife migrations—out of Amboseli with the rains and back in the dry season. Beginning in the early 1990s, the pastoralists around the park began occupying their seasonal settlements year-round. The upshot was that during the rains, livestock no longer migrated and were tempting prey for hungry carnivores. The shortage of wildlife prey during the rains was compounded by the sharp drop in resident browsing species in the park due to the loss of woodlands and woody vegetation. The losses of resident browsers exaggerated the shortage of prey during the migrations and made livestock more tempting yet to carnivores.

Another factor contributing to the increasing carnivore-human conflict is the growing numbers of lions and hyenas in Amboseli. The numbers of wildebeest, zebra and buffalo in Amboseli more than doubled during the 1980s, giving the carnivores far more prey to feed on. Despite this increase in the prey base, carnivore numbers did not increase as quickly as expected. The main reason was that under the Wildlife Conservation and Management Department that ran Amboseli until 1989, anti-poaching was lax and little effort was made to prevent herders poisoning lions and hyenas. In 1989 when Kenya Wildlife Service took over management, security and conflict management quickly improved and carnivore numbers increased sharply. The growth in lion numbers that started with increasing security in the early 1990s increased yet again in the mid to late 2000s as the wild herbivore numbers concentrated more than ever in the basin due to intensifying drought and growing pasture shortages.

The situation in Amboseli cannot be remedied easily, and certainly not by ignoring the root causes of the cause of the wildlife collapse and habitat degradation. It will take several years for wildlife and livestock numbers to rebound. In the meantime carnivore attacks on livestock will continue and perhaps increase if hyenas switch to stock killing during rains now that the drought carcasses have disappeared. That is, the attacks will continue unless prevented by barricades that KWS and conservation groups build around night corrals to curb predation. And if night corrals are successful carnivore numbers will drop to the size the wild herbivore prey base can support.

Another factor that further complicates the picture is the response of wild herbivores to hungry carnivores. Zebra and wildebeest now regularly move out of the park at night. The nocturnal migration is something not previously seen in Amboseli. Coupled with a heavy exodus of zebra and wildebeest during the rains and the partial resumption of movement by buffalo not seen in decades, the avoidance of the park suggests that elevated predation pressure is a major deterrent.

The interlinked ecological and social events driving the collapse of the herbivore populations in Amboseli and the tightening oscillations and rising carnivore-human conflict stress why the restoration and conservation of Amboseli must be considered broadly, rather than narrowly from the perspective of wild herbivores, carnivores or livestock. The fate of the carnivores is closely bound to the recovery of the wildlife herds and in turn the recovery of the rangelands, the Amboseli swamps and the woodland. The behavior of the herbivores in response to higher predation risk has a strong bearing on the level of use wildlife makes of the park, which will in turn affect the tourism appeal of Amboseli and perhaps visitation.

The complex and continuing fallout of the drought and long-term habitat deterioration as well as changing social and economic situation among the Maasai in the Amboseli region calls for a reexamination of the Amboseli Ecosystem Management Plan. Habitat and species recovery plans will depend most of all on tackling the deep seated threats to the Amboseli ecosystem.

The Fluctuating Fortunes of Wildlife

In this report we review the counts of large herbivores in and around Amboseli National Park since the 2009 drought and consider some ecological and social consequences.

The fluctuating fortunes of wildlife, predators, and pastoralists in Amboseli.

The sample ground counts and total aerial counts (Fig. 1 and Fig 2) show the heavy drought losses wildebeest, zebra and buffalo, the main prey species of Amboseli’s large carnivores, suffered in the last four months of 2009 drought. The remaining herds moved out with the rains of December 2009, leaving a few dozen animals in the park. In the following dry season we had expected only the remnant herds surviving the drought to return to Amboseli. Quite unexpectedly, the remnant herds were accompanied by an influx of over 1,400 wildebeest and several hundred zebra from adjacent populations, most likely Tsavo and northern Tanzania. The herbivore populations built up to a peak of some 1,500 wildebeest and 2,500 zebra in the late dry season of 2010. During the November-December rains the numbers fell sharply again with the migrations. The migrants were expected back at the beginning of the dry season in January of 2011, but unexpected cyclone rains fell across the region and kept them out of the park in the wet season dispersal areas.

The sample ground counts and total aerial counts (Fig. 1 and Fig 2) show the heavy drought losses wildebeest, zebra and buffalo, the main prey species of Amboseli’s large carnivores, suffered in the last four months of 2009 drought. The remaining herds moved out with the rains of December 2009, leaving a few dozen animals in the park. In the following dry season we had expected only the remnant herds surviving the drought to return to Amboseli. Quite unexpectedly, the remnant herds were accompanied by an influx of over 1,400 wildebeest and several hundred zebra from adjacent populations, most likely Tsavo and northern Tanzania. The herbivore populations built up to a peak of some 1,500 wildebeest and 2,500 zebra in the late dry season of 2010. During the November-December rains the numbers fell sharply again with the migrations. The migrants were expected back at the beginning of the dry season in January of 2011, but unexpected cyclone rains fell across the region and kept them out of the park in the wet season dispersal areas.

The February total aerial count of the park gave the lowest wildlife numbers recorded in 43 years of ACP surveys. Wildebeest numbers dropped to 10 and zebra 71. Buffalo numbers dropped from over 200 to 90, meaning that more than half the population moved out of the basin with the unseasonal rains. Such an outward migration of buffalo from the park has not been recorded since the late 1960s and early 1970s. The March count showed little increase in herbivore numbers. The low counts mean that Amboseli is sure to skip the January to March dry season and that the migrations will extend from November until the end of the long rains in May or June. The long absence of wild herbivores will confront lions and hyenas with extreme food deprivation and raise the specter of conflict with livestock once more.

The extreme fluctuations in prey species in Amboseli since 2009, coupled with the longer term changes since the early 1990s, largely explains the growing conflict between large carnivores and Maasai herders around the park, as detailed in earlier reports.

The precipitous drop in lion and hyena prey species in the Amboseli Basin since 2009 explains the sharp increase in carnivore-human conflict since the 2009 drought, as predicted at the Emergency Drought Workshop of December 2009. Carnivore attacks on livestock began immediately after the drought, coinciding with the wildebeest and zebra migrations and the return of the Maasai with their remnant cattle herds. At that stage, nearly all attacks on livestock were by lions unable to find wild prey in the vicinity. Contrary to expectations, hyenas did not attack livestock. They were getting by on the 10,000 or so carcasses left by the drought.

The return of the migrant herds in the dry season of 2010, accompanied by an influx of animals from Tsavo and Tanzania, gave the carnivores enough to feed on without killing livestock. The drop in zebra and wildebeest numbers with the October rains of 2009 led to a further round of livestock attacks, this time with hyenas joining lions after they ran out of drought carcasses. A total of 274 livestock were killed by predators in September and October 2009. Hyenas killed 103 animals and lions 57. The unseasonal rains in February kept the migrant herds out of Amboseli, resulting in a continuation of carnivore attacks on livestock when they would otherwise have dropped off with the return of the migrants.

The rising conflict between large carnivores and people in Amboseli is explained in large part by the collapse of their prey base in the 2009 drought. When the prey-based dropped by three quarters in a matter of months, the lion and hyena population would have dropped sharply in the following year was it not for the lion attacks on livestock and hyena dependence on drought carcasses. As it is, the lion population has fallen by nearly a half due to reprisal killing by herders. But several other ecological and social changes over the last two decades and more contribute to the ecological and social fallout of the 2009 drought.

The most important factor explaining the rising attacks on livestock during the rains is permanent settlement. Until the early 1990s, Maasai pastoralists moved their livestock in tandem with the wildlife migrations—out of Amboseli with the rains and back in the dry season. Beginning in the early 1990s, the pastoralists around the park began occupying their seasonal settlements year-round. The upshot was that during the rains, livestock no longer migrated and were tempting prey for hungry carnivores. The shortage of wildlife prey during the rains was compounded by the sharp drop in resident browsing species in the park due to the loss of woodlands and woody vegetation. The losses of resident browsers exaggerated the shortage of prey during the migrations and made livestock more tempting yet to carnivores.

Another factor contributing to the increasing carnivore-human conflict is the growing numbers of lions and hyenas in Amboseli. The numbers of wildebeest, zebra and buffalo in Amboseli more than doubled during the 1980s, giving the carnivores far more prey to feed on. Despite this increase in the prey base, carnivore numbers did not increase as quickly as expected. The main reason was that under the Wildlife Conservation and Management Department that ran Amboseli until 1989, anti-poaching was lax and little effort was made to prevent herders poisoning lions and hyenas. In 1989 when Kenya Wildlife Service took over management, security and conflict management quickly improved and carnivore numbers increased sharply. The growth in lion numbers that started with increasing security in the early 1990s increased yet again in the mid to late 2000s as the wild herbivore numbers concentrated more than ever in the basin due to intensifying drought and growing pasture shortages.

The situation in Amboseli cannot be remedied easily, and certainly not by ignoring the root causes of the cause of the wildlife collapse and habitat degradation. It will take several years for wildlife and livestock numbers to rebound. In the meantime carnivore attacks on livestock will continue and perhaps increase if hyenas switch to stock killing during rains now that the drought carcasses have disappeared. That is, the attacks will continue unless prevented by barricades that KWS and conservation groups build around night corrals to curb predation. And if night corrals are successful carnivore numbers will drop to the size the wild herbivore prey base can support.

Another factor that further complicates the picture is the response of wild herbivores to hungry carnivores. Zebra and wildebeest now regularly move out of the park at night. The nocturnal migration is something not previously seen in Amboseli. Coupled with a heavy exodus of zebra and wildebeest during the rains and the partial resumption of movement by buffalo not seen in decades, the avoidance of the park suggests that elevated predation pressure is a major deterrent.

The interlinked ecological and social events driving the collapse of the herbivore populations in Amboseli and the tightening oscillations and rising carnivore-human conflict stress why the restoration and conservation of Amboseli must be considered broadly, rather than narrowly from the perspective of wild herbivores, carnivores or livestock. The fate of the carnivores is closely bound to the recovery of the wildlife herds and in turn the recovery of the rangelands, the Amboseli swamps and the woodland. The behavior of the herbivores in response to higher predation risk has a strong bearing on the level of use wildlife makes of the park, which will in turn affect the tourism appeal of Amboseli and perhaps visitation.

The complex and continuing fallout of the drought and long-term habitat deterioration as well as changing social and economic situation among the Maasai in the Amboseli region calls for a reexamination of the Amboseli Ecosystem Management Plan. Habitat and species recovery plans will depend most of all on tackling the deep seated threats to the Amboseli ecosystem.

The fluctuating fortunes of wildlife, predators, and pastoralists in Amboseli.

The sample ground counts and total aerial counts (Fig. 1 and Fig 2) show the heavy drought losses wildebeest, zebra and buffalo, the main prey species of Amboseli’s large carnivores, suffered in the last four months of 2009 drought. The remaining herds moved out with the rains of December 2009, leaving a few dozen animals in the park. In the following dry season we had expected only the remnant herds surviving the drought to return to Amboseli. Quite unexpectedly, the remnant herds were accompanied by an influx of over 1,400 wildebeest and several hundred zebra from adjacent populations, most likely Tsavo and northern Tanzania. The herbivore populations built up to a peak of some 1,500 wildebeest and 2,500 zebra in the late dry season of 2010. During the November-December rains the numbers fell sharply again with the migrations. The migrants were expected back at the beginning of the dry season in January of 2011, but unexpected cyclone rains fell across the region and kept them out of the park in the wet season dispersal areas.

The sample ground counts and total aerial counts (Fig. 1 and Fig 2) show the heavy drought losses wildebeest, zebra and buffalo, the main prey species of Amboseli’s large carnivores, suffered in the last four months of 2009 drought. The remaining herds moved out with the rains of December 2009, leaving a few dozen animals in the park. In the following dry season we had expected only the remnant herds surviving the drought to return to Amboseli. Quite unexpectedly, the remnant herds were accompanied by an influx of over 1,400 wildebeest and several hundred zebra from adjacent populations, most likely Tsavo and northern Tanzania. The herbivore populations built up to a peak of some 1,500 wildebeest and 2,500 zebra in the late dry season of 2010. During the November-December rains the numbers fell sharply again with the migrations. The migrants were expected back at the beginning of the dry season in January of 2011, but unexpected cyclone rains fell across the region and kept them out of the park in the wet season dispersal areas.

The February total aerial count of the park gave the lowest wildlife numbers recorded in 43 years of ACP surveys. Wildebeest numbers dropped to 10 and zebra 71. Buffalo numbers dropped from over 200 to 90, meaning that more than half the population moved out of the basin with the unseasonal rains. Such an outward migration of buffalo from the park has not been recorded since the late 1960s and early 1970s. The March count showed little increase in herbivore numbers. The low counts mean that Amboseli is sure to skip the January to March dry season and that the migrations will extend from November until the end of the long rains in May or June. The long absence of wild herbivores will confront lions and hyenas with extreme food deprivation and raise the specter of conflict with livestock once more.

The extreme fluctuations in prey species in Amboseli since 2009, coupled with the longer term changes since the early 1990s, largely explains the growing conflict between large carnivores and Maasai herders around the park, as detailed in earlier reports.

The precipitous drop in lion and hyena prey species in the Amboseli Basin since 2009 explains the sharp increase in carnivore-human conflict since the 2009 drought, as predicted at the Emergency Drought Workshop of December 2009. Carnivore attacks on livestock began immediately after the drought, coinciding with the wildebeest and zebra migrations and the return of the Maasai with their remnant cattle herds. At that stage, nearly all attacks on livestock were by lions unable to find wild prey in the vicinity. Contrary to expectations, hyenas did not attack livestock. They were getting by on the 10,000 or so carcasses left by the drought.

The return of the migrant herds in the dry season of 2010, accompanied by an influx of animals from Tsavo and Tanzania, gave the carnivores enough to feed on without killing livestock. The drop in zebra and wildebeest numbers with the October rains of 2009 led to a further round of livestock attacks, this time with hyenas joining lions after they ran out of drought carcasses. A total of 274 livestock were killed by predators in September and October 2009. Hyenas killed 103 animals and lions 57. The unseasonal rains in February kept the migrant herds out of Amboseli, resulting in a continuation of carnivore attacks on livestock when they would otherwise have dropped off with the return of the migrants.

The rising conflict between large carnivores and people in Amboseli is explained in large part by the collapse of their prey base in the 2009 drought. When the prey-based dropped by three quarters in a matter of months, the lion and hyena population would have dropped sharply in the following year was it not for the lion attacks on livestock and hyena dependence on drought carcasses. As it is, the lion population has fallen by nearly a half due to reprisal killing by herders. But several other ecological and social changes over the last two decades and more contribute to the ecological and social fallout of the 2009 drought.

The most important factor explaining the rising attacks on livestock during the rains is permanent settlement. Until the early 1990s, Maasai pastoralists moved their livestock in tandem with the wildlife migrations—out of Amboseli with the rains and back in the dry season. Beginning in the early 1990s, the pastoralists around the park began occupying their seasonal settlements year-round. The upshot was that during the rains, livestock no longer migrated and were tempting prey for hungry carnivores. The shortage of wildlife prey during the rains was compounded by the sharp drop in resident browsing species in the park due to the loss of woodlands and woody vegetation. The losses of resident browsers exaggerated the shortage of prey during the migrations and made livestock more tempting yet to carnivores.

Another factor contributing to the increasing carnivore-human conflict is the growing numbers of lions and hyenas in Amboseli. The numbers of wildebeest, zebra and buffalo in Amboseli more than doubled during the 1980s, giving the carnivores far more prey to feed on. Despite this increase in the prey base, carnivore numbers did not increase as quickly as expected. The main reason was that under the Wildlife Conservation and Management Department that ran Amboseli until 1989, anti-poaching was lax and little effort was made to prevent herders poisoning lions and hyenas. In 1989 when Kenya Wildlife Service took over management, security and conflict management quickly improved and carnivore numbers increased sharply. The growth in lion numbers that started with increasing security in the early 1990s increased yet again in the mid to late 2000s as the wild herbivore numbers concentrated more than ever in the basin due to intensifying drought and growing pasture shortages.

The situation in Amboseli cannot be remedied easily, and certainly not by ignoring the root causes of the cause of the wildlife collapse and habitat degradation. It will take several years for wildlife and livestock numbers to rebound. In the meantime carnivore attacks on livestock will continue and perhaps increase if hyenas switch to stock killing during rains now that the drought carcasses have disappeared. That is, the attacks will continue unless prevented by barricades that KWS and conservation groups build around night corrals to curb predation. And if night corrals are successful carnivore numbers will drop to the size the wild herbivore prey base can support.

Another factor that further complicates the picture is the response of wild herbivores to hungry carnivores. Zebra and wildebeest now regularly move out of the park at night. The nocturnal migration is something not previously seen in Amboseli. Coupled with a heavy exodus of zebra and wildebeest during the rains and the partial resumption of movement by buffalo not seen in decades, the avoidance of the park suggests that elevated predation pressure is a major deterrent.

The interlinked ecological and social events driving the collapse of the herbivore populations in Amboseli and the tightening oscillations and rising carnivore-human conflict stress why the restoration and conservation of Amboseli must be considered broadly, rather than narrowly from the perspective of wild herbivores, carnivores or livestock. The fate of the carnivores is closely bound to the recovery of the wildlife herds and in turn the recovery of the rangelands, the Amboseli swamps and the woodland. The behavior of the herbivores in response to higher predation risk has a strong bearing on the level of use wildlife makes of the park, which will in turn affect the tourism appeal of Amboseli and perhaps visitation.

The complex and continuing fallout of the drought and long-term habitat deterioration as well as changing social and economic situation among the Maasai in the Amboseli region calls for a reexamination of the Amboseli Ecosystem Management Plan. Habitat and species recovery plans will depend most of all on tackling the deep seated threats to the Amboseli ecosystem.