The MOSAIC field mission to the Amazon region, following a previous mission to East Africa in September, took place from October 19 to November 5, 2024. The mission covered key sites in the tri-border area between Brazil, Colombia, and Peru, as well as the Brazil–French Guiana border near Oiapoque in the state of Amapá. With representation from over 15 institutions, participants included researchers, medical doctors, computer scientists, project managers, and others. Although it was considered the dry season, we experienced several rainy days, and the Amazon River was a breathtaking sight, especially for first-time visitors from East Africa.

Just as in the Amboseli ecosystem in East Africa, the Amazon region also sees extensive community involvement in research projects, particularly with indigenous communities. In the Amazon, local groups are deeply engaged in health initiatives such as indigenous mid-wife support and addressing diseases such as malaria, tuberculosis, and dengue. Our mission began with a presentation to stakeholders, including government representatives and educational institutions, held in Leticia, Colombia. Stakeholders presented their work at the National University of Colombia, which has a fully functioning Faculty of Indigenous Studies. Here, local Ticuna people not only participate actively in these projects but also pursue graduate studies to better understand and support their communities. This is similar to the engagement seen in East Africa, where local Maasai communities are involved in both research and development efforts that address local issues.

An hour-long boat ride along the Amazon River, the primary mode of transportation in the Amazonas region, took participants to Amacayacu National Natural Park along the river. There, park staff engage in conservation and ecological monitoring using tools like SMART. Local communities are permitted to use forest resources sustainably, with regulations in place for certain activities to ensure responsible use. One significant collaborative focus is joint data analysis and the development of a unified database to consolidate the dispersed data collected within the Amazonian Park. The data integration system in the Amboseli analysis lab could serve as a model for this effort in the Amazon, and this was agreed upon during the visit. Notably, an island formed from Amazon River silting about ten years ago, which the locals have yet to name.

After another 40-minute boat ride, participants arrived at Puerto Nariño, a dolphin conservancy, tourism, and education centre managed by the local community. Here, locals are involved in reforestation efforts, not only planting trees but also nurturing them to maturity. At the Omacha Amazon Conservation Centre, data is available on tree growth, dolphin populations, and the general environment, alongside several publications on the region’s ecological status. The Amboseli program similarly publishes regular environmental reports on the health of the Amboseli ecosystem.

In the border town of Oiapoque, a 12-hour bus ride from Macapá, local Wayãpi indigenous communities are integrated into the health support system. Many cross into French Guiana to receive specialized healthcare services provided by the French government at the Saint-Georges Health Center, which is supported by Cayenne Hospital. Challenges in registering individuals accessing these services are common, much like those faced by cross-border communities such as the Maasai along the Kenya-Tanzania border. Recently, there has been a rise in lifestyle-related diseases among indigenous communities, along with some cases of sexually transmitted infections. However, HIV prevalence remains notably low within these communities.

The Laboratory de Fronteira in the border town of Tabatinga, located between Brazil and Colombia, has implemented a dashboard system for monitoring respiratory viruses, helping to identify and track the spread of diseases like influenza and others. This surveillance allows health officials to determine which virus variants are circulating, enabling them to take appropriate actions to treat patients and prevent further transmission. This monitoring process supports informed decision-making and the development of health strategies to safeguard the local population.

With support from the MOSAIC project, the Amboseli Conservation Program (ACP) and the African Conservation Centre are developing a similar dashboard for Kajiado County, in southern Kenya. This system will track various disease indicators for livestock and wildlife, monitor land degradation, and assess crop and grass suitability. The ACP has developed a data visualization tool to analyse long-term data collected from the Amboseli ecosystem. This tool provides near real-time information on environmental conditions by synthesizing satellite data, along with data on livestock and wildlife body condition, milk yields, livestock market prices, rainfall, and other key variables. These insights are crucial for local decision-making by herders and other stakeholders.

(https://amboseliprogram.org/)

Realtime interactive dashboards, supported by the MOSAIC project, are being developed by the Amboseli Conservation Program (ACP) and the African Conservation Centre for Kajiado County in southern Kenya. These dashboards will track disease indicators for livestock and wildlife, monitor land degradation, and assess the suitability of crops and grasslands. The field mission in the Amazon region was highly informative, with several parallels drawn to East Africa. The Amazon ecosystem is under threat and must remain intact, as opening it up to uses like livestock farming contrasts with the situation in East Africa, where rangelands must stay open to sustain biodiversity.

As for the MOSAIC project, the multisite approach to implementation is both interesting and complex. The Amazon group has made significant progress in engaging stakeholders, particularly in the public health sector. Communities are well-integrated into health provider programs, and information is documented for potential analysis.

However, there is limited focus on ecological monitoring, an area where MOSAIC East Africa has excelled. Efforts are ongoing to upgrade the health database in East Africa, with plans to collaborate with local stakeholders to incorporate their expertise in health data analysis and presentation. A partnership with Jomo Kenyatta University of Agriculture and Technology is in development to expand the secondary health data collected by the MOSAIC East African team. The MOSAIC Amazon team will leverage the ecological methodologies used in East Africa to conduct sample ecological monitoring and questionnaire surveys.

The next steps for the MOSAIC project include identifying individual “One Health” indicators and designing a composite indicator. This may prove challenging, as there is no single “One Health” approach—it’s a collection of diverse health indicators, even among indigenous communities, as observed in both the Amazon and East Africa. Mathematical models can help integrate these concepts and analyze the deficiencies in applying a “One Health” approach to overall well-being.

The MOSAIC field mission to the Amazon region, following a previous mission to East Africa in September, took place from October 19 to November 5, 2024. The mission covered key sites in the tri-border area between Brazil, Colombia, and Peru, as well as the Brazil–French Guiana border near Oiapoque in the state of Amapá. With representation from over 15 institutions, participants included researchers, medical doctors, computer scientists, project managers, and others. Although it was considered the dry season, we experienced several rainy days, and the Amazon River was a breathtaking sight, especially for first-time visitors from East Africa.

Just as in the Amboseli ecosystem in East Africa, the Amazon region also sees extensive community involvement in research projects, particularly with indigenous communities. In the Amazon, local groups are deeply engaged in health initiatives such as indigenous mid-wife support and addressing diseases such as malaria, tuberculosis, and dengue. Our mission began with a presentation to stakeholders, including government representatives and educational institutions, held in Leticia, Colombia. Stakeholders presented their work at the National University of Colombia, which has a fully functioning Faculty of Indigenous Studies. Here, local Ticuna people not only participate actively in these projects but also pursue graduate studies to better understand and support their communities. This is similar to the engagement seen in East Africa, where local Maasai communities are involved in both research and development efforts that address local issues.

An hour-long boat ride along the Amazon River, the primary mode of transportation in the Amazonas region, took participants to Amacayacu National Natural Park along the river. There, park staff engage in conservation and ecological monitoring using tools like SMART. Local communities are permitted to use forest resources sustainably, with regulations in place for certain activities to ensure responsible use. One significant collaborative focus is joint data analysis and the development of a unified database to consolidate the dispersed data collected within the Amazonian Park. The data integration system in the Amboseli analysis lab could serve as a model for this effort in the Amazon, and this was agreed upon during the visit. Notably, an island formed from Amazon River silting about ten years ago, which the locals have yet to name.

After another 40-minute boat ride, participants arrived at Puerto Nariño, a dolphin conservancy, tourism, and education centre managed by the local community. Here, locals are involved in reforestation efforts, not only planting trees but also nurturing them to maturity. At the Omacha Amazon Conservation Centre, data is available on tree growth, dolphin populations, and the general environment, alongside several publications on the region’s ecological status. The Amboseli program similarly publishes regular environmental reports on the health of the Amboseli ecosystem.

In the border town of Oiapoque, a 12-hour bus ride from Macapá, local Wayãpi indigenous communities are integrated into the health support system. Many cross into French Guiana to receive specialized healthcare services provided by the French government at the Saint-Georges Health Center, which is supported by Cayenne Hospital. Challenges in registering individuals accessing these services are common, much like those faced by cross-border communities such as the Maasai along the Kenya-Tanzania border. Recently, there has been a rise in lifestyle-related diseases among indigenous communities, along with some cases of sexually transmitted infections. However, HIV prevalence remains notably low within these communities.

The Laboratory de Fronteira in the border town of Tabatinga, located between Brazil and Colombia, has implemented a dashboard system for monitoring respiratory viruses, helping to identify and track the spread of diseases like influenza and others. This surveillance allows health officials to determine which virus variants are circulating, enabling them to take appropriate actions to treat patients and prevent further transmission. This monitoring process supports informed decision-making and the development of health strategies to safeguard the local population.

With support from the MOSAIC project, the Amboseli Conservation Program (ACP) and the African Conservation Centre are developing a similar dashboard for Kajiado County, in southern Kenya. This system will track various disease indicators for livestock and wildlife, monitor land degradation, and assess crop and grass suitability. The ACP has developed a data visualization tool to analyse long-term data collected from the Amboseli ecosystem. This tool provides near real-time information on environmental conditions by synthesizing satellite data, along with data on livestock and wildlife body condition, milk yields, livestock market prices, rainfall, and other key variables. These insights are crucial for local decision-making by herders and other stakeholders.

(https://amboseliprogram.org/)

Realtime interactive dashboards, supported by the MOSAIC project, are being developed by the Amboseli Conservation Program (ACP) and the African Conservation Centre for Kajiado County in southern Kenya. These dashboards will track disease indicators for livestock and wildlife, monitor land degradation, and assess the suitability of crops and grasslands. The field mission in the Amazon region was highly informative, with several parallels drawn to East Africa. The Amazon ecosystem is under threat and must remain intact, as opening it up to uses like livestock farming contrasts with the situation in East Africa, where rangelands must stay open to sustain biodiversity.

As for the MOSAIC project, the multisite approach to implementation is both interesting and complex. The Amazon group has made significant progress in engaging stakeholders, particularly in the public health sector. Communities are well-integrated into health provider programs, and information is documented for potential analysis.

However, there is limited focus on ecological monitoring, an area where MOSAIC East Africa has excelled. Efforts are ongoing to upgrade the health database in East Africa, with plans to collaborate with local stakeholders to incorporate their expertise in health data analysis and presentation. A partnership with Jomo Kenyatta University of Agriculture and Technology is in development to expand the secondary health data collected by the MOSAIC East African team. The MOSAIC Amazon team will leverage the ecological methodologies used in East Africa to conduct sample ecological monitoring and questionnaire surveys.

The next steps for the MOSAIC project include identifying individual “One Health” indicators and designing a composite indicator. This may prove challenging, as there is no single “One Health” approach—it’s a collection of diverse health indicators, even among indigenous communities, as observed in both the Amazon and East Africa. Mathematical models can help integrate these concepts and analyze the deficiencies in applying a “One Health” approach to overall well-being.

The MOSAIC field mission to the Amazon region, following a previous mission to East Africa in September, took place from October 19 to November 5, 2024. The mission covered key sites in the tri-border area between Brazil, Colombia, and Peru, as well as the Brazil–French Guiana border near Oiapoque in the state of Amapá. With representation from over 15 institutions, participants included researchers, medical doctors, computer scientists, project managers, and others. Although it was considered the dry season, we experienced several rainy days, and the Amazon River was a breathtaking sight, especially for first-time visitors from East Africa.

Just as in the Amboseli ecosystem in East Africa, the Amazon region also sees extensive community involvement in research projects, particularly with indigenous communities. In the Amazon, local groups are deeply engaged in health initiatives such as indigenous mid-wife support and addressing diseases such as malaria, tuberculosis, and dengue. Our mission began with a presentation to stakeholders, including government representatives and educational institutions, held in Leticia, Colombia. Stakeholders presented their work at the National University of Colombia, which has a fully functioning Faculty of Indigenous Studies. Here, local Ticuna people not only participate actively in these projects but also pursue graduate studies to better understand and support their communities. This is similar to the engagement seen in East Africa, where local Maasai communities are involved in both research and development efforts that address local issues.

An hour-long boat ride along the Amazon River, the primary mode of transportation in the Amazonas region, took participants to Amacayacu National Natural Park along the river. There, park staff engage in conservation and ecological monitoring using tools like SMART. Local communities are permitted to use forest resources sustainably, with regulations in place for certain activities to ensure responsible use. One significant collaborative focus is joint data analysis and the development of a unified database to consolidate the dispersed data collected within the Amazonian Park. The data integration system in the Amboseli analysis lab could serve as a model for this effort in the Amazon, and this was agreed upon during the visit. Notably, an island formed from Amazon River silting about ten years ago, which the locals have yet to name.

After another 40-minute boat ride, participants arrived at Puerto Nariño, a dolphin conservancy, tourism, and education centre managed by the local community. Here, locals are involved in reforestation efforts, not only planting trees but also nurturing them to maturity. At the Omacha Amazon Conservation Centre, data is available on tree growth, dolphin populations, and the general environment, alongside several publications on the region’s ecological status. The Amboseli program similarly publishes regular environmental reports on the health of the Amboseli ecosystem.

In the border town of Oiapoque, a 12-hour bus ride from Macapá, local Wayãpi indigenous communities are integrated into the health support system. Many cross into French Guiana to receive specialized healthcare services provided by the French government at the Saint-Georges Health Center, which is supported by Cayenne Hospital. Challenges in registering individuals accessing these services are common, much like those faced by cross-border communities such as the Maasai along the Kenya-Tanzania border. Recently, there has been a rise in lifestyle-related diseases among indigenous communities, along with some cases of sexually transmitted infections. However, HIV prevalence remains notably low within these communities.

The Laboratory de Fronteira in the border town of Tabatinga, located between Brazil and Colombia, has implemented a dashboard system for monitoring respiratory viruses, helping to identify and track the spread of diseases like influenza and others. This surveillance allows health officials to determine which virus variants are circulating, enabling them to take appropriate actions to treat patients and prevent further transmission. This monitoring process supports informed decision-making and the development of health strategies to safeguard the local population.

With support from the MOSAIC project, the Amboseli Conservation Program (ACP) and the African Conservation Centre are developing a similar dashboard for Kajiado County, in southern Kenya. This system will track various disease indicators for livestock and wildlife, monitor land degradation, and assess crop and grass suitability. The ACP has developed a data visualization tool to analyse long-term data collected from the Amboseli ecosystem. This tool provides near real-time information on environmental conditions by synthesizing satellite data, along with data on livestock and wildlife body condition, milk yields, livestock market prices, rainfall, and other key variables. These insights are crucial for local decision-making by herders and other stakeholders.

(https://amboseliprogram.org/)

Realtime interactive dashboards, supported by the MOSAIC project, are being developed by the Amboseli Conservation Program (ACP) and the African Conservation Centre for Kajiado County in southern Kenya. These dashboards will track disease indicators for livestock and wildlife, monitor land degradation, and assess the suitability of crops and grasslands. The field mission in the Amazon region was highly informative, with several parallels drawn to East Africa. The Amazon ecosystem is under threat and must remain intact, as opening it up to uses like livestock farming contrasts with the situation in East Africa, where rangelands must stay open to sustain biodiversity.

As for the MOSAIC project, the multisite approach to implementation is both interesting and complex. The Amazon group has made significant progress in engaging stakeholders, particularly in the public health sector. Communities are well-integrated into health provider programs, and information is documented for potential analysis.

However, there is limited focus on ecological monitoring, an area where MOSAIC East Africa has excelled. Efforts are ongoing to upgrade the health database in East Africa, with plans to collaborate with local stakeholders to incorporate their expertise in health data analysis and presentation. A partnership with Jomo Kenyatta University of Agriculture and Technology is in development to expand the secondary health data collected by the MOSAIC East African team. The MOSAIC Amazon team will leverage the ecological methodologies used in East Africa to conduct sample ecological monitoring and questionnaire surveys.

The next steps for the MOSAIC project include identifying individual “One Health” indicators and designing a composite indicator. This may prove challenging, as there is no single “One Health” approach—it’s a collection of diverse health indicators, even among indigenous communities, as observed in both the Amazon and East Africa. Mathematical models can help integrate these concepts and analyze the deficiencies in applying a “One Health” approach to overall well-being.

The MOSAIC field mission to the Amazon region, following a previous mission to East Africa in September, took place from October 19 to November 5, 2024. The mission covered key sites in the tri-border area between Brazil, Colombia, and Peru, as well as the Brazil–French Guiana border near Oiapoque in the state of Amapá. With representation from over 15 institutions, participants included researchers, medical doctors, computer scientists, project managers, and others. Although it was considered the dry season, we experienced several rainy days, and the Amazon River was a breathtaking sight, especially for first-time visitors from East Africa.

Just as in the Amboseli ecosystem in East Africa, the Amazon region also sees extensive community involvement in research projects, particularly with indigenous communities. In the Amazon, local groups are deeply engaged in health initiatives such as indigenous mid-wife support and addressing diseases such as malaria, tuberculosis, and dengue. Our mission began with a presentation to stakeholders, including government representatives and educational institutions, held in Leticia, Colombia. Stakeholders presented their work at the National University of Colombia, which has a fully functioning Faculty of Indigenous Studies. Here, local Ticuna people not only participate actively in these projects but also pursue graduate studies to better understand and support their communities. This is similar to the engagement seen in East Africa, where local Maasai communities are involved in both research and development efforts that address local issues.

An hour-long boat ride along the Amazon River, the primary mode of transportation in the Amazonas region, took participants to Amacayacu National Natural Park along the river. There, park staff engage in conservation and ecological monitoring using tools like SMART. Local communities are permitted to use forest resources sustainably, with regulations in place for certain activities to ensure responsible use. One significant collaborative focus is joint data analysis and the development of a unified database to consolidate the dispersed data collected within the Amazonian Park. The data integration system in the Amboseli analysis lab could serve as a model for this effort in the Amazon, and this was agreed upon during the visit. Notably, an island formed from Amazon River silting about ten years ago, which the locals have yet to name.

After another 40-minute boat ride, participants arrived at Puerto Nariño, a dolphin conservancy, tourism, and education centre managed by the local community. Here, locals are involved in reforestation efforts, not only planting trees but also nurturing them to maturity. At the Omacha Amazon Conservation Centre, data is available on tree growth, dolphin populations, and the general environment, alongside several publications on the region’s ecological status. The Amboseli program similarly publishes regular environmental reports on the health of the Amboseli ecosystem.

In the border town of Oiapoque, a 12-hour bus ride from Macapá, local Wayãpi indigenous communities are integrated into the health support system. Many cross into French Guiana to receive specialized healthcare services provided by the French government at the Saint-Georges Health Center, which is supported by Cayenne Hospital. Challenges in registering individuals accessing these services are common, much like those faced by cross-border communities such as the Maasai along the Kenya-Tanzania border. Recently, there has been a rise in lifestyle-related diseases among indigenous communities, along with some cases of sexually transmitted infections. However, HIV prevalence remains notably low within these communities.

The Laboratory de Fronteira in the border town of Tabatinga, located between Brazil and Colombia, has implemented a dashboard system for monitoring respiratory viruses, helping to identify and track the spread of diseases like influenza and others. This surveillance allows health officials to determine which virus variants are circulating, enabling them to take appropriate actions to treat patients and prevent further transmission. This monitoring process supports informed decision-making and the development of health strategies to safeguard the local population.

With support from the MOSAIC project, the Amboseli Conservation Program (ACP) and the African Conservation Centre are developing a similar dashboard for Kajiado County, in southern Kenya. This system will track various disease indicators for livestock and wildlife, monitor land degradation, and assess crop and grass suitability. The ACP has developed a data visualization tool to analyse long-term data collected from the Amboseli ecosystem. This tool provides near real-time information on environmental conditions by synthesizing satellite data, along with data on livestock and wildlife body condition, milk yields, livestock market prices, rainfall, and other key variables. These insights are crucial for local decision-making by herders and other stakeholders.

(https://amboseliprogram.org/)

Realtime interactive dashboards, supported by the MOSAIC project, are being developed by the Amboseli Conservation Program (ACP) and the African Conservation Centre for Kajiado County in southern Kenya. These dashboards will track disease indicators for livestock and wildlife, monitor land degradation, and assess the suitability of crops and grasslands. The field mission in the Amazon region was highly informative, with several parallels drawn to East Africa. The Amazon ecosystem is under threat and must remain intact, as opening it up to uses like livestock farming contrasts with the situation in East Africa, where rangelands must stay open to sustain biodiversity.

As for the MOSAIC project, the multisite approach to implementation is both interesting and complex. The Amazon group has made significant progress in engaging stakeholders, particularly in the public health sector. Communities are well-integrated into health provider programs, and information is documented for potential analysis.

However, there is limited focus on ecological monitoring, an area where MOSAIC East Africa has excelled. Efforts are ongoing to upgrade the health database in East Africa, with plans to collaborate with local stakeholders to incorporate their expertise in health data analysis and presentation. A partnership with Jomo Kenyatta University of Agriculture and Technology is in development to expand the secondary health data collected by the MOSAIC East African team. The MOSAIC Amazon team will leverage the ecological methodologies used in East Africa to conduct sample ecological monitoring and questionnaire surveys.

The next steps for the MOSAIC project include identifying individual “One Health” indicators and designing a composite indicator. This may prove challenging, as there is no single “One Health” approach—it’s a collection of diverse health indicators, even among indigenous communities, as observed in both the Amazon and East Africa. Mathematical models can help integrate these concepts and analyze the deficiencies in applying a “One Health” approach to overall well-being.

For over 50 years, we’ve been pioneering conservation work in Amboseli sustained habitats, livelihoods and resilience through collaboration amid environmental changes, protecting biodiversity.

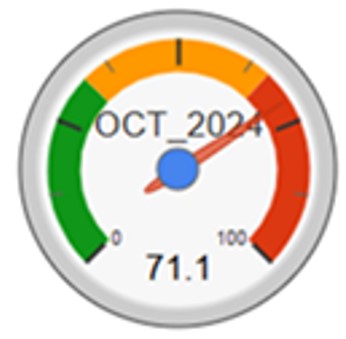

Current grazing pressure percentage.

Amboseli Conservation Program

P.O Box 15289-00509 or 62844-00200

Nairobi, Kenya.

Tel/Fax: +254 20 891360 / 891751

Email: acc@acc.or.ke

Amboseli Conservation Program

P.O Box 15289-00509 or 62844-00200

Nairobi, Kenya.

Tel/Fax: +254 20 891360 / 891751

Email: acc@acc.or.ke