Introduction

Amboseli became world renowned in the 1950s as the setting for Where No Vulture’s Fly, a film of the struggles to create Kenya’s national parks. Famous long-horn rhinos, large-tusked elephants, teeming herds of wildlife and elegant yellow fever trees set against the background of Kilimanjaro, Amboseli drew visitors from around the world. Then, in the mid-1950s, the fever trees began dying. Conservationists blamed the Maasai for overgrazing Amboseli and pushed government to create a national park.

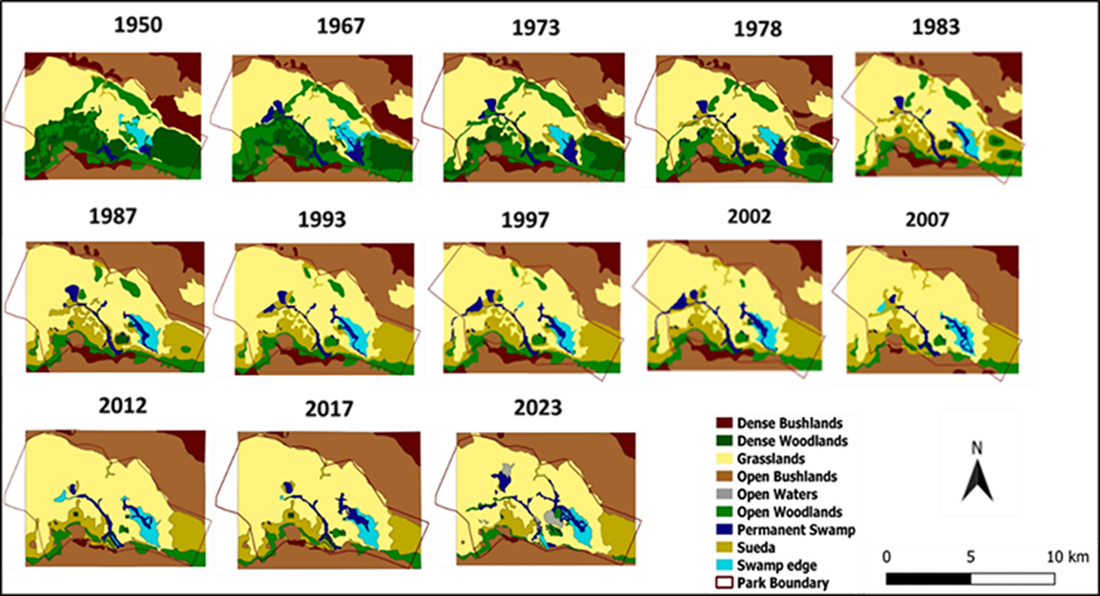

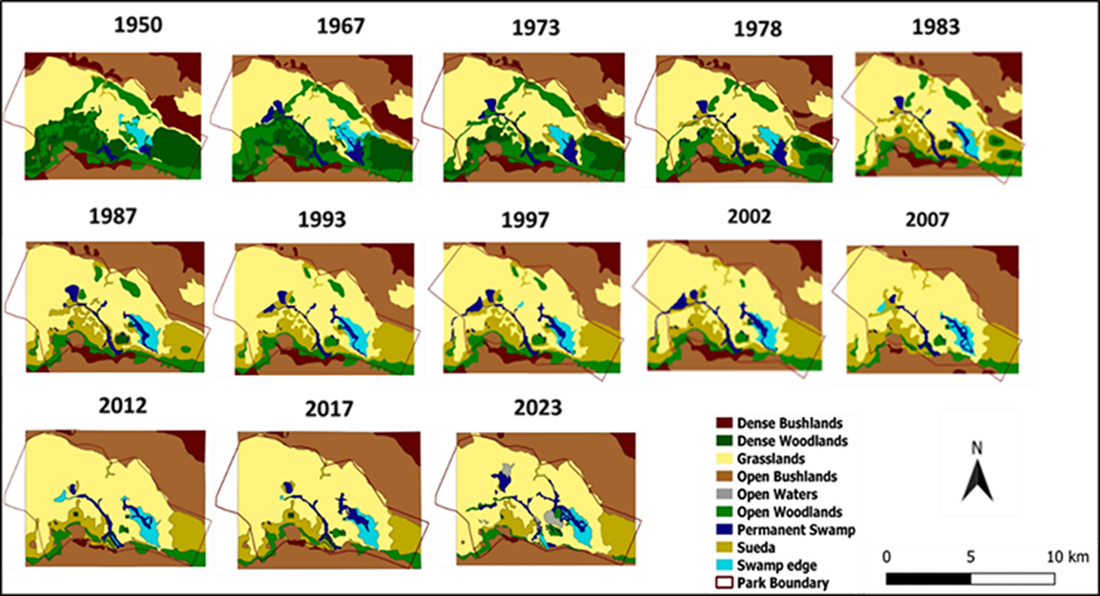

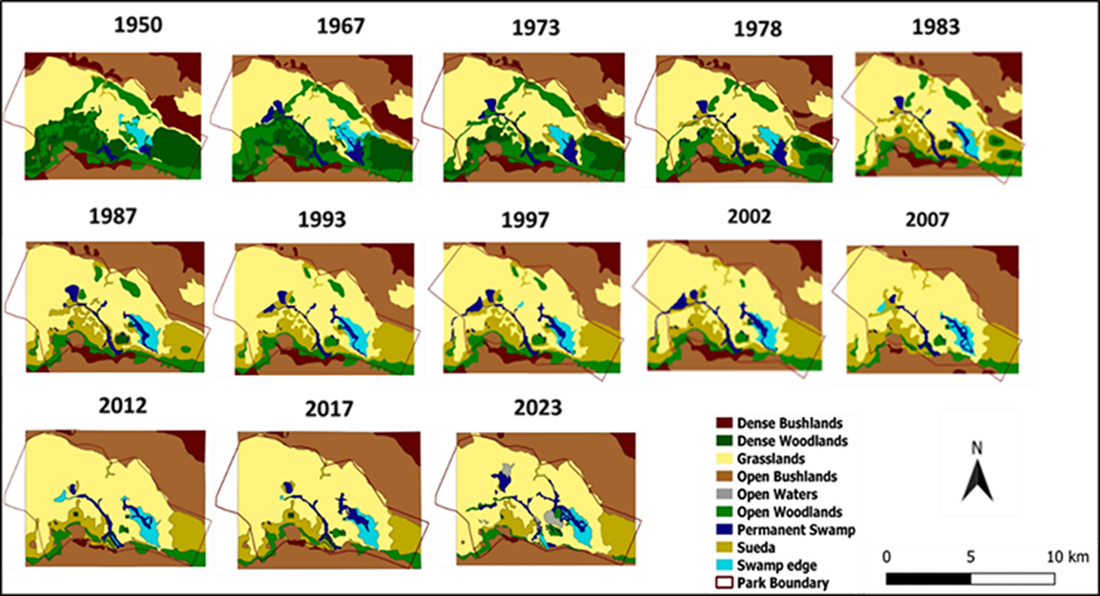

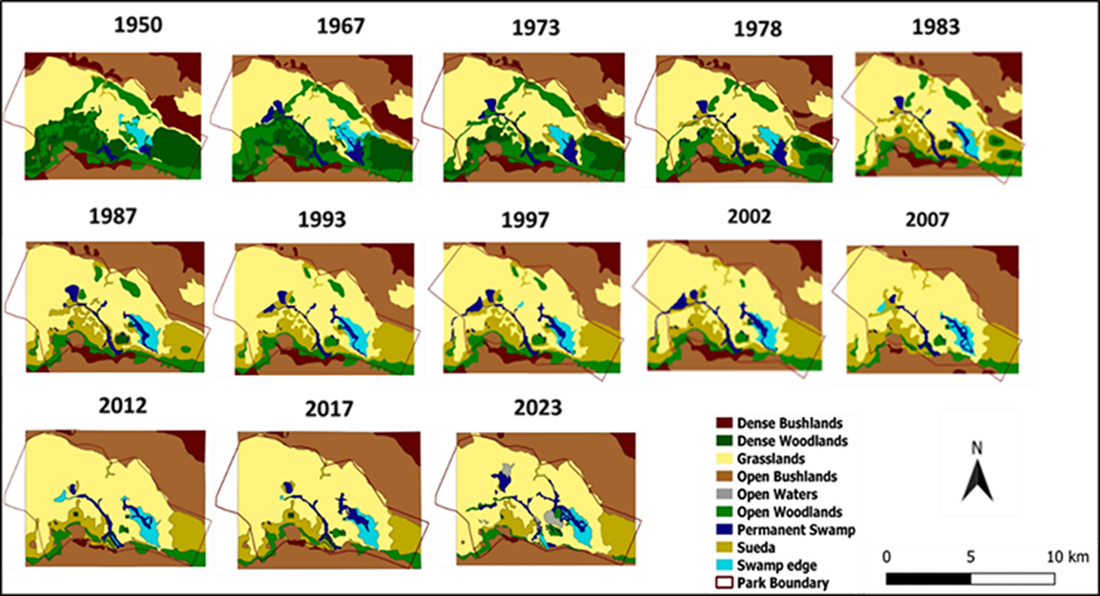

The Amboseli Conservation Program (ACP) began an ecological study of Amboseli in 1967, focusing on wildlife migrations and the dying woodlands. The program mapped twenty-eight distinctive vegetation zones as a baseline for monitoring future changes. The changes were mapped every five years or so in the ensuring six decades. The program set up permanent plots in the mid-1970s to monitor pasture conditions and seasonal changes in species composition of trees, shrubs, herbs and grasses. Details of vegetation mapping and monitoring methods can be found in technical reports published by the ACP team.

The study on the woodland die-off exonerated the Maasai as the cause and initially implicated a rising water table4. Later long-term exclosure experiments showed elephants alone to be the cause. The studies showed the woodlands changes to be symptomatic of far larger ecological changes underway in Amboseli.

The studies showed plant diversity and productivity have declined, biomass turning over faster, and ecological resilience declining. Human activity has now overtaken rainfall in driving the seasonal rhythms and decadal fluctuations in plants, livestock and wildlife.

The aim of the ACP bulletins is to produce timely information on the current status and ecological changes in Amboseli for use in planning and management of the Amboseli ecosystem and national park. This bulletin updates earlier publications on the long-term changes in vegetation and the underlying causes. We give vegetation trends and present results in graphic form for ease of viewing. We conclude with comment on the causes of change and the implications for the management of Amboseli.

Download the Amboseli vegetation bulletin below.

Amboseli Vegetation Bulletin March 2025

Introduction

Amboseli became world renowned in the 1950s as the setting for Where No Vulture’s Fly, a film of the struggles to create Kenya’s national parks. Famous long-horn rhinos, large-tusked elephants, teeming herds of wildlife and elegant yellow fever trees set against the background of Kilimanjaro, Amboseli drew visitors from around the world. Then, in the mid-1950s, the fever trees began dying. Conservationists blamed the Maasai for overgrazing Amboseli and pushed government to create a national park.

The Amboseli Conservation Program (ACP) began an ecological study of Amboseli in 1967, focusing on wildlife migrations and the dying woodlands. The program mapped twenty-eight distinctive vegetation zones as a baseline for monitoring future changes. The changes were mapped every five years or so in the ensuring six decades. The program set up permanent plots in the mid-1970s to monitor pasture conditions and seasonal changes in species composition of trees, shrubs, herbs and grasses. Details of vegetation mapping and monitoring methods can be found in technical reports published by the ACP team.

The study on the woodland die-off exonerated the Maasai as the cause and initially implicated a rising water table4. Later long-term exclosure experiments showed elephants alone to be the cause. The studies showed the woodlands changes to be symptomatic of far larger ecological changes underway in Amboseli.

The studies showed plant diversity and productivity have declined, biomass turning over faster, and ecological resilience declining. Human activity has now overtaken rainfall in driving the seasonal rhythms and decadal fluctuations in plants, livestock and wildlife.

The aim of the ACP bulletins is to produce timely information on the current status and ecological changes in Amboseli for use in planning and management of the Amboseli ecosystem and national park. This bulletin updates earlier publications on the long-term changes in vegetation and the underlying causes. We give vegetation trends and present results in graphic form for ease of viewing. We conclude with comment on the causes of change and the implications for the management of Amboseli.

Download the Amboseli vegetation bulletin below.

Amboseli Vegetation Bulletin March 2025

Introduction

Amboseli became world renowned in the 1950s as the setting for Where No Vulture’s Fly, a film of the struggles to create Kenya’s national parks. Famous long-horn rhinos, large-tusked elephants, teeming herds of wildlife and elegant yellow fever trees set against the background of Kilimanjaro, Amboseli drew visitors from around the world. Then, in the mid-1950s, the fever trees began dying. Conservationists blamed the Maasai for overgrazing Amboseli and pushed government to create a national park.

The Amboseli Conservation Program (ACP) began an ecological study of Amboseli in 1967, focusing on wildlife migrations and the dying woodlands. The program mapped twenty-eight distinctive vegetation zones as a baseline for monitoring future changes. The changes were mapped every five years or so in the ensuring six decades. The program set up permanent plots in the mid-1970s to monitor pasture conditions and seasonal changes in species composition of trees, shrubs, herbs and grasses. Details of vegetation mapping and monitoring methods can be found in technical reports published by the ACP team.

The study on the woodland die-off exonerated the Maasai as the cause and initially implicated a rising water table4. Later long-term exclosure experiments showed elephants alone to be the cause. The studies showed the woodlands changes to be symptomatic of far larger ecological changes underway in Amboseli.

The studies showed plant diversity and productivity have declined, biomass turning over faster, and ecological resilience declining. Human activity has now overtaken rainfall in driving the seasonal rhythms and decadal fluctuations in plants, livestock and wildlife.

The aim of the ACP bulletins is to produce timely information on the current status and ecological changes in Amboseli for use in planning and management of the Amboseli ecosystem and national park. This bulletin updates earlier publications on the long-term changes in vegetation and the underlying causes. We give vegetation trends and present results in graphic form for ease of viewing. We conclude with comment on the causes of change and the implications for the management of Amboseli.

Download the Amboseli vegetation bulletin below.

Amboseli Vegetation Bulletin March 2025

Introduction

Amboseli became world renowned in the 1950s as the setting for Where No Vulture’s Fly, a film of the struggles to create Kenya’s national parks. Famous long-horn rhinos, large-tusked elephants, teeming herds of wildlife and elegant yellow fever trees set against the background of Kilimanjaro, Amboseli drew visitors from around the world. Then, in the mid-1950s, the fever trees began dying. Conservationists blamed the Maasai for overgrazing Amboseli and pushed government to create a national park.

The Amboseli Conservation Program (ACP) began an ecological study of Amboseli in 1967, focusing on wildlife migrations and the dying woodlands. The program mapped twenty-eight distinctive vegetation zones as a baseline for monitoring future changes. The changes were mapped every five years or so in the ensuring six decades. The program set up permanent plots in the mid-1970s to monitor pasture conditions and seasonal changes in species composition of trees, shrubs, herbs and grasses. Details of vegetation mapping and monitoring methods can be found in technical reports published by the ACP team.

The study on the woodland die-off exonerated the Maasai as the cause and initially implicated a rising water table4. Later long-term exclosure experiments showed elephants alone to be the cause. The studies showed the woodlands changes to be symptomatic of far larger ecological changes underway in Amboseli.

The studies showed plant diversity and productivity have declined, biomass turning over faster, and ecological resilience declining. Human activity has now overtaken rainfall in driving the seasonal rhythms and decadal fluctuations in plants, livestock and wildlife.

The aim of the ACP bulletins is to produce timely information on the current status and ecological changes in Amboseli for use in planning and management of the Amboseli ecosystem and national park. This bulletin updates earlier publications on the long-term changes in vegetation and the underlying causes. We give vegetation trends and present results in graphic form for ease of viewing. We conclude with comment on the causes of change and the implications for the management of Amboseli.

Download the Amboseli vegetation bulletin below.

Amboseli Vegetation Bulletin March 2025

Amboseli Conservation Program

P.O Box 15289-00509 or 62844-00200

Nairobi, Kenya.

Tel/Fax: +254 20 891360 / 891751

Email: acc@acc.or.ke