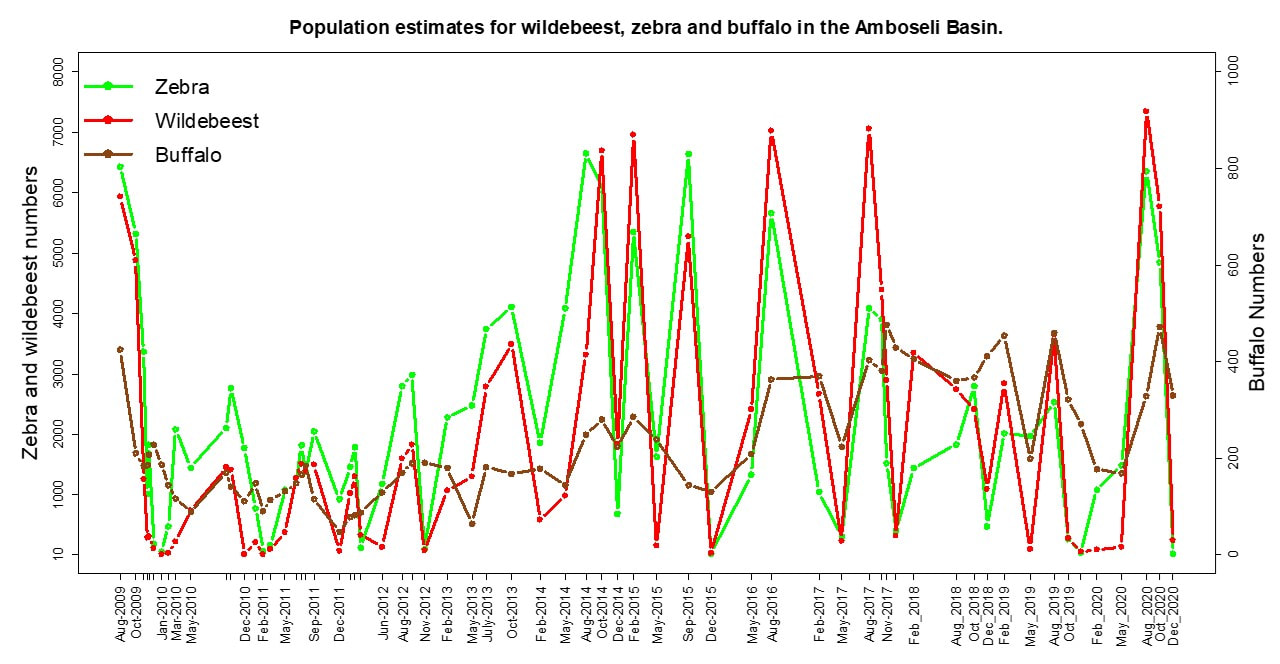

We began regularly counting wildlife in the Amboseli Basin in 2009 in anticipation of the severe drought in the course of the year. The counts of 700 square kilometer Amboseli Basin were designed to catalogue the drought and subsequent recovery in far greater detail than we could glean from the large-scale aerial counts of the 8,500 square kilometer ecosystem censuses once a year. The ground counts of live and dead animals proved timely.

The wildlife and livestock losses to drought in 2009 became so alarming that we convened an emergency meeting in of the Amboseli Ecosystem Trust, Kenya Wildlife Service and conservation organizations in December 2009. At the meeting we presented the extreme drought losses: over 95 of the wildebeest and two thirds of the zebra and cattle died, died in the preceding few months. The two hundred remaining wildebeest of the 6,000 at the start of the year were in imminent risk of extinction. We also forecast heavy predation on cattle around Amboseli National Park once wildlife left on migrations. Unfortunately, our warnings went unheeded and many lions were killed by herders suffering heavy cattle losses.

The unexpected good news is that wildlife bounced back far faster than the slow recovery we projected due to heavy predation on the small surviving herds, by 2020 wildlife numbers had recovered, and even exceeded those at the start of 2009. The graph below shows the strong recovery of wildebeest and zebra between the 2009 and 2014. Buffalo, which seldom migrated in the rains, suffered far heavier predation than zebra and wildebeest and were slower to bounce back but had also recovered their pre-drought levels by 2017.

The faster than expected recovery from the extreme drought of 2009 resulted from a fortuitous influx of wildebeest and zebra from Tsavo National Park and Ngaserai in Tanzania. Had the links to these wildlife areas been cut off, Amboseli’s wildlife would have taken years longer to recover, and wildebeest would likely have gone extinct. The recovery shows just how important is the connection between wildlife areas and parks become more isolated and vulnerable to drought and other hazards. The connections to adjacent wildlife areas have been incorporated into the Amboseli Ecosystem Management Plan and Amboseli National Park Plan 2020-2030.

For a fuller description of the drought see David Western. The Worst Drought. Turning Point or Tipping Point. Swara 2010: 3 16-20, for an account of the drought.

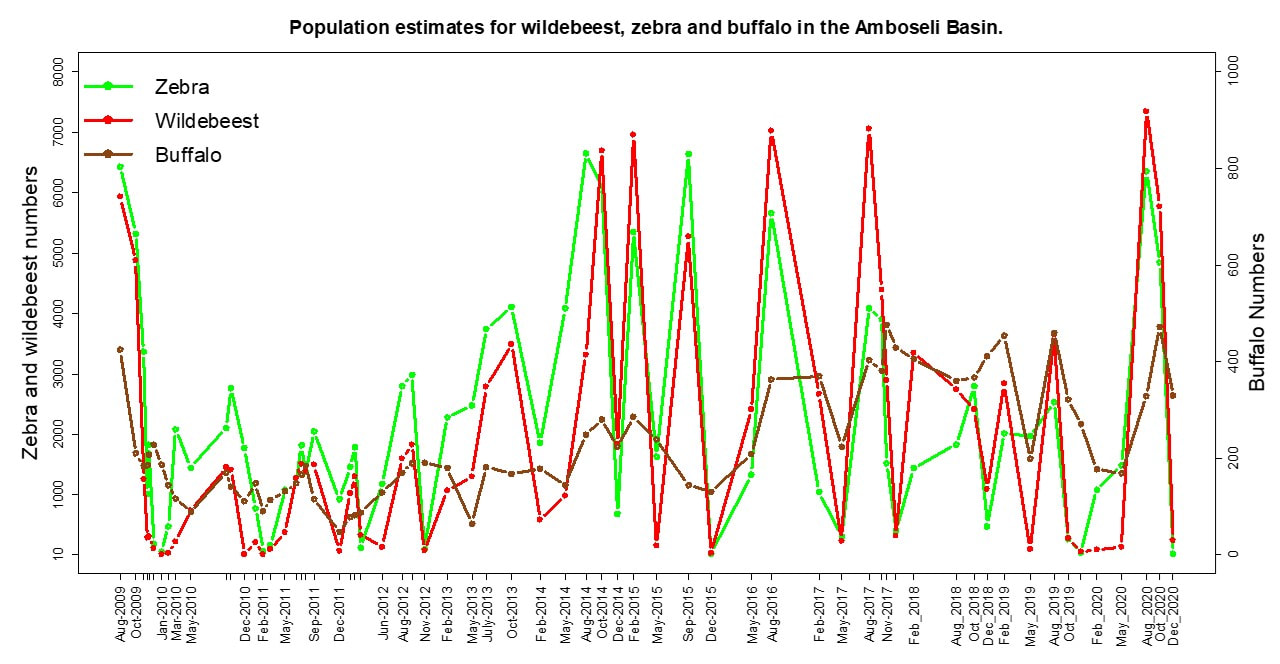

We began regularly counting wildlife in the Amboseli Basin in 2009 in anticipation of the severe drought in the course of the year. The counts of 700 square kilometer Amboseli Basin were designed to catalogue the drought and subsequent recovery in far greater detail than we could glean from the large-scale aerial counts of the 8,500 square kilometer ecosystem censuses once a year. The ground counts of live and dead animals proved timely.

The wildlife and livestock losses to drought in 2009 became so alarming that we convened an emergency meeting in of the Amboseli Ecosystem Trust, Kenya Wildlife Service and conservation organizations in December 2009. At the meeting we presented the extreme drought losses: over 95 of the wildebeest and two thirds of the zebra and cattle died, died in the preceding few months. The two hundred remaining wildebeest of the 6,000 at the start of the year were in imminent risk of extinction. We also forecast heavy predation on cattle around Amboseli National Park once wildlife left on migrations. Unfortunately, our warnings went unheeded and many lions were killed by herders suffering heavy cattle losses.

The unexpected good news is that wildlife bounced back far faster than the slow recovery we projected due to heavy predation on the small surviving herds, by 2020 wildlife numbers had recovered, and even exceeded those at the start of 2009. The graph below shows the strong recovery of wildebeest and zebra between the 2009 and 2014. Buffalo, which seldom migrated in the rains, suffered far heavier predation than zebra and wildebeest and were slower to bounce back but had also recovered their pre-drought levels by 2017.

The faster than expected recovery from the extreme drought of 2009 resulted from a fortuitous influx of wildebeest and zebra from Tsavo National Park and Ngaserai in Tanzania. Had the links to these wildlife areas been cut off, Amboseli’s wildlife would have taken years longer to recover, and wildebeest would likely have gone extinct. The recovery shows just how important is the connection between wildlife areas and parks become more isolated and vulnerable to drought and other hazards. The connections to adjacent wildlife areas have been incorporated into the Amboseli Ecosystem Management Plan and Amboseli National Park Plan 2020-2030.

For a fuller description of the drought see David Western. The Worst Drought. Turning Point or Tipping Point. Swara 2010: 3 16-20, for an account of the drought.

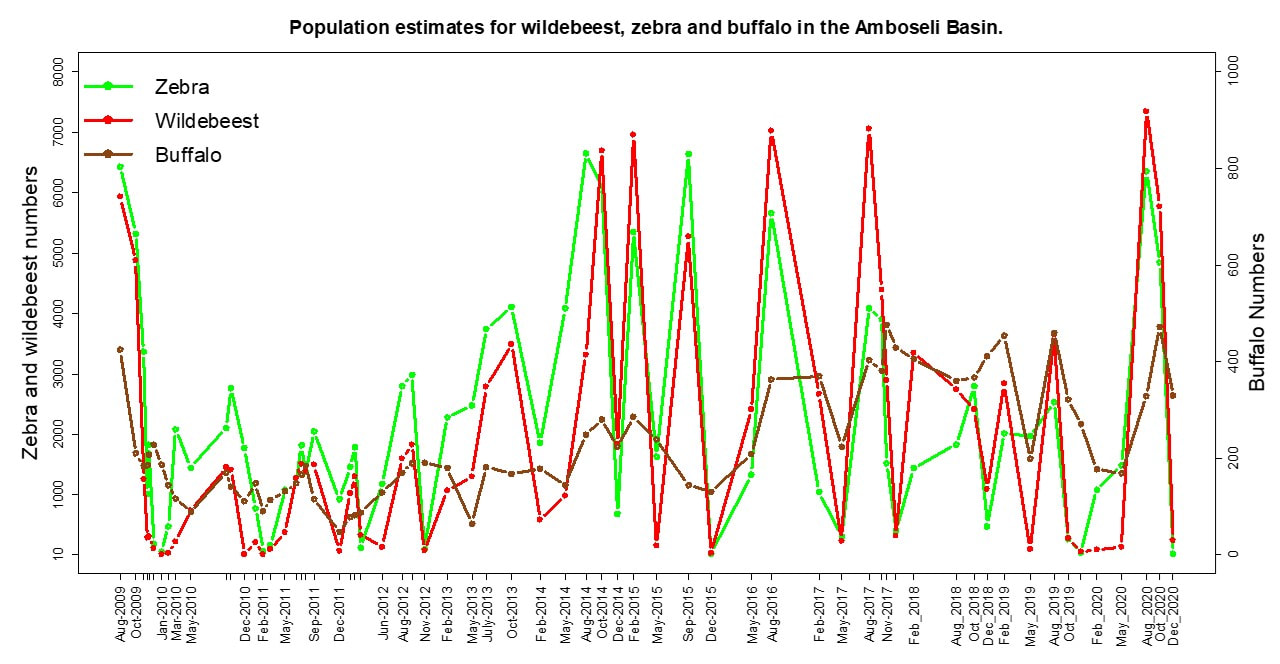

We began regularly counting wildlife in the Amboseli Basin in 2009 in anticipation of the severe drought in the course of the year. The counts of 700 square kilometer Amboseli Basin were designed to catalogue the drought and subsequent recovery in far greater detail than we could glean from the large-scale aerial counts of the 8,500 square kilometer ecosystem censuses once a year. The ground counts of live and dead animals proved timely.

The wildlife and livestock losses to drought in 2009 became so alarming that we convened an emergency meeting in of the Amboseli Ecosystem Trust, Kenya Wildlife Service and conservation organizations in December 2009. At the meeting we presented the extreme drought losses: over 95 of the wildebeest and two thirds of the zebra and cattle died, died in the preceding few months. The two hundred remaining wildebeest of the 6,000 at the start of the year were in imminent risk of extinction. We also forecast heavy predation on cattle around Amboseli National Park once wildlife left on migrations. Unfortunately, our warnings went unheeded and many lions were killed by herders suffering heavy cattle losses.

The unexpected good news is that wildlife bounced back far faster than the slow recovery we projected due to heavy predation on the small surviving herds, by 2020 wildlife numbers had recovered, and even exceeded those at the start of 2009. The graph below shows the strong recovery of wildebeest and zebra between the 2009 and 2014. Buffalo, which seldom migrated in the rains, suffered far heavier predation than zebra and wildebeest and were slower to bounce back but had also recovered their pre-drought levels by 2017.

The faster than expected recovery from the extreme drought of 2009 resulted from a fortuitous influx of wildebeest and zebra from Tsavo National Park and Ngaserai in Tanzania. Had the links to these wildlife areas been cut off, Amboseli’s wildlife would have taken years longer to recover, and wildebeest would likely have gone extinct. The recovery shows just how important is the connection between wildlife areas and parks become more isolated and vulnerable to drought and other hazards. The connections to adjacent wildlife areas have been incorporated into the Amboseli Ecosystem Management Plan and Amboseli National Park Plan 2020-2030.

For a fuller description of the drought see David Western. The Worst Drought. Turning Point or Tipping Point. Swara 2010: 3 16-20, for an account of the drought.

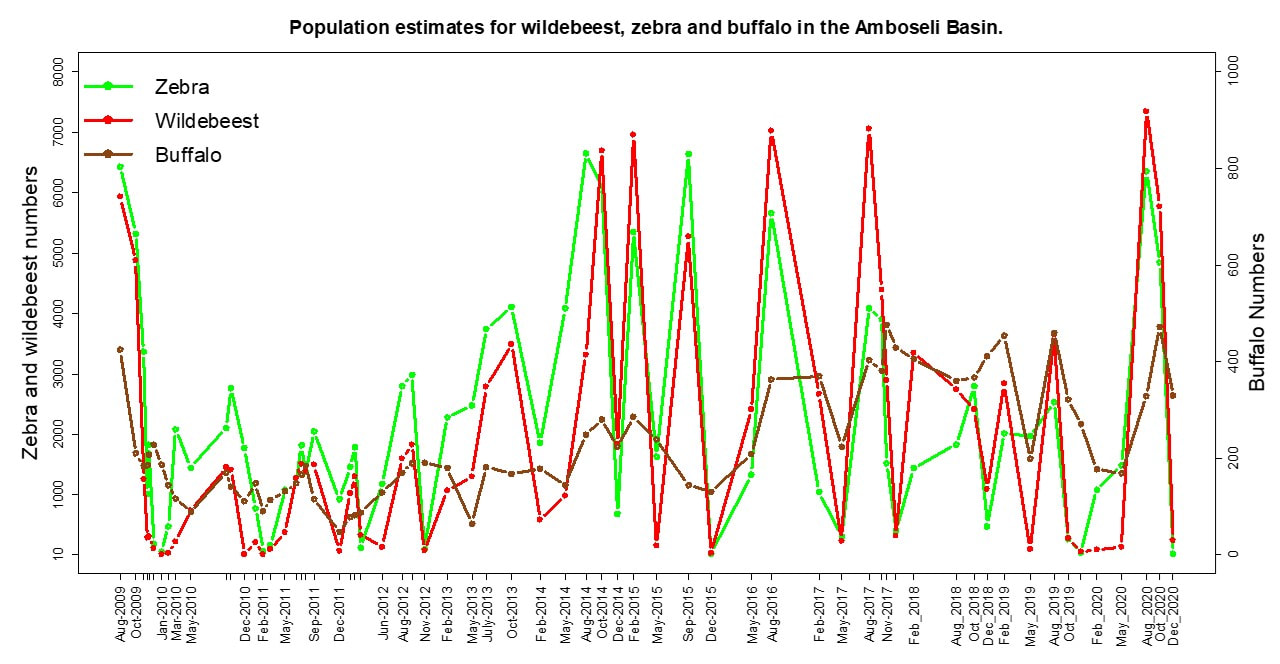

We began regularly counting wildlife in the Amboseli Basin in 2009 in anticipation of the severe drought in the course of the year. The counts of 700 square kilometer Amboseli Basin were designed to catalogue the drought and subsequent recovery in far greater detail than we could glean from the large-scale aerial counts of the 8,500 square kilometer ecosystem censuses once a year. The ground counts of live and dead animals proved timely.

The wildlife and livestock losses to drought in 2009 became so alarming that we convened an emergency meeting in of the Amboseli Ecosystem Trust, Kenya Wildlife Service and conservation organizations in December 2009. At the meeting we presented the extreme drought losses: over 95 of the wildebeest and two thirds of the zebra and cattle died, died in the preceding few months. The two hundred remaining wildebeest of the 6,000 at the start of the year were in imminent risk of extinction. We also forecast heavy predation on cattle around Amboseli National Park once wildlife left on migrations. Unfortunately, our warnings went unheeded and many lions were killed by herders suffering heavy cattle losses.

The unexpected good news is that wildlife bounced back far faster than the slow recovery we projected due to heavy predation on the small surviving herds, by 2020 wildlife numbers had recovered, and even exceeded those at the start of 2009. The graph below shows the strong recovery of wildebeest and zebra between the 2009 and 2014. Buffalo, which seldom migrated in the rains, suffered far heavier predation than zebra and wildebeest and were slower to bounce back but had also recovered their pre-drought levels by 2017.

The faster than expected recovery from the extreme drought of 2009 resulted from a fortuitous influx of wildebeest and zebra from Tsavo National Park and Ngaserai in Tanzania. Had the links to these wildlife areas been cut off, Amboseli’s wildlife would have taken years longer to recover, and wildebeest would likely have gone extinct. The recovery shows just how important is the connection between wildlife areas and parks become more isolated and vulnerable to drought and other hazards. The connections to adjacent wildlife areas have been incorporated into the Amboseli Ecosystem Management Plan and Amboseli National Park Plan 2020-2030.

For a fuller description of the drought see David Western. The Worst Drought. Turning Point or Tipping Point. Swara 2010: 3 16-20, for an account of the drought.

For over 50 years, we’ve been pioneering conservation work in Amboseli sustained habitats, livelihoods and resilience through collaboration amid environmental changes, protecting biodiversity.

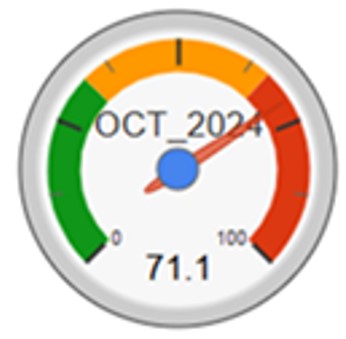

Current grazing pressure percentage.

Amboseli Conservation Program

P.O Box 15289-00509 or 62844-00200

Nairobi, Kenya.

Tel/Fax: +254 20 891360 / 891751

Email: acc@acc.or.ke

Amboseli Conservation Program

P.O Box 15289-00509 or 62844-00200

Nairobi, Kenya.

Tel/Fax: +254 20 891360 / 891751

Email: acc@acc.or.ke