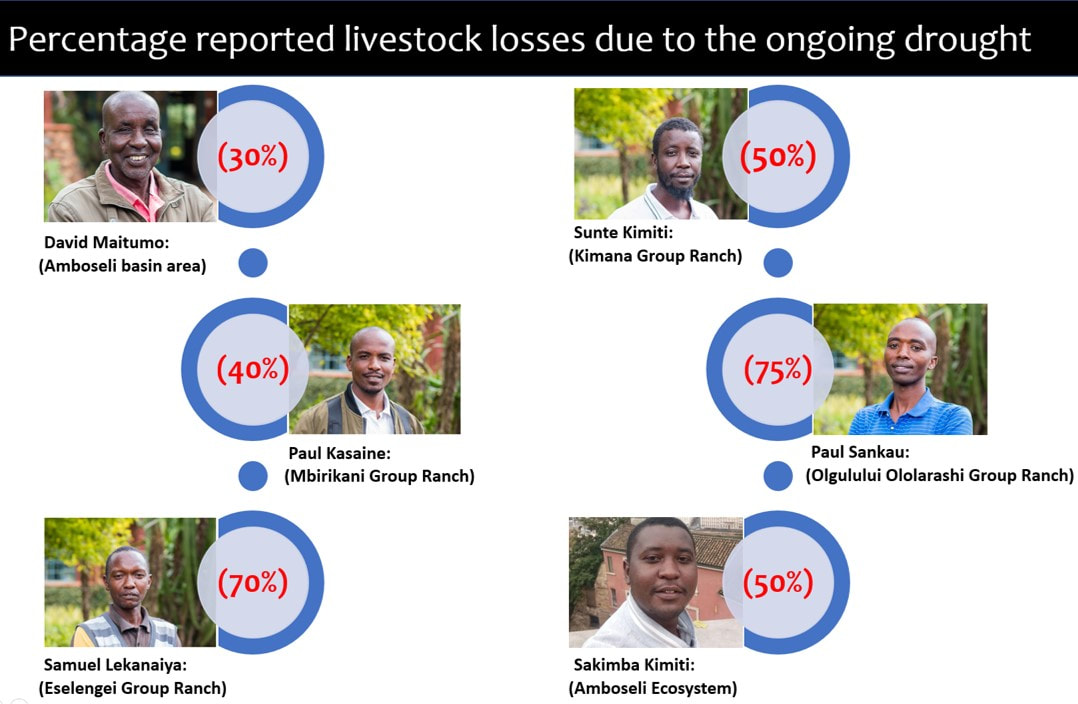

Many herders and crop farmers, based on my observations in Eselengei group ranch, have never experienced such a severe drought. To supplement the lack of grass, livestock are given commercial feeds and hay. A sack of flour meal costs between Ksh. 1600/= and Ksh. 3000/=, depending on quality. Following some rain, herds migrated to Magadi, Narok, Machakos, Kiboko, and our neighboring country, Tanzania; they are almost all returning to their permanent homesteads to feed the remaining livestock with commercial feeds.

Very few herds have lactating cows, and those that do, don’t sell their milk; instead, it is used for household purposes. Older calves are separated from their mothers as the drought bites on. The current livestock body condition ranges from 1-4 on a scale of 1-9, with 9 being the best. A mature animal cost around Ksh. 30,000, while sheep and goats’ cost Ksh. 4,000.

Many children have not attended school because their parents rely on rainfall to cultivate subsistence crops. Those in school are the children of parents who rely on irrigation and formal employment. Herders in Eselengei estimate that they have lost 70% of their livestock.

Sunte Kimiti:

The entire Amboseli ecosystem is experiencing a severe drought, which has resulted in the deaths of livestock and wildlife. As a result, pastoralists have been forced to migrate all over the region, some as far as Narok and the coastal lowlands.

Livestock are starving, prompting herders to look for areas where it has recently rained, such as the Chyulu Hills, Ukambani and Kibwezi. The cost of purchasing livestock feed and grass has been a financial burden for many people. Herders in Kimana who once had over 200 cows now have less than 80.

The dairy production from cattle has also been severely impacted, with a lack of pastures causing a decline in the livestock’s body condition. The market prices for livestock have decreased due to their condition and falling demand. The herders are struggling to pay for their children’s education. Some parents have been forced to withdraw their children from school due to a lack of fees.

Paul Kasaine:

Paul Sankau:

The pastoralists have had a difficult time. There hasn’t been any rain in three years. Only light showers have fallen during the months when rain is traditionally expected. As a result, there are few or no grasses in all areas. Reports from the OOGR indicate that some herders have lost close to 75% of their livestock. Wildlife has not been spared either. Many zebras, gazelles, giraffes, wildebeests, and even elephants have died as a result of the drought.

Since vegetation has disappeared and almost all grasslands now remain bare grounds, herders are buying crushed cones locally known as pumba, in addition to hay, and cone plants from farms under irrigation to feed our livestock. With all these efforts livestock are still dying. A double loss!

Following the light rain showers, herders have taken their livestock to the Chyulu hills, Oltepesi, Enkii, Oloile, Lemong’o, Olng’arua Loosinet, and Ngoirienito. The livestock body condition scores remain below average. Their prices continue to drop as children get back to school. The drought has also led to malnutrition in children as milk yields dry up.

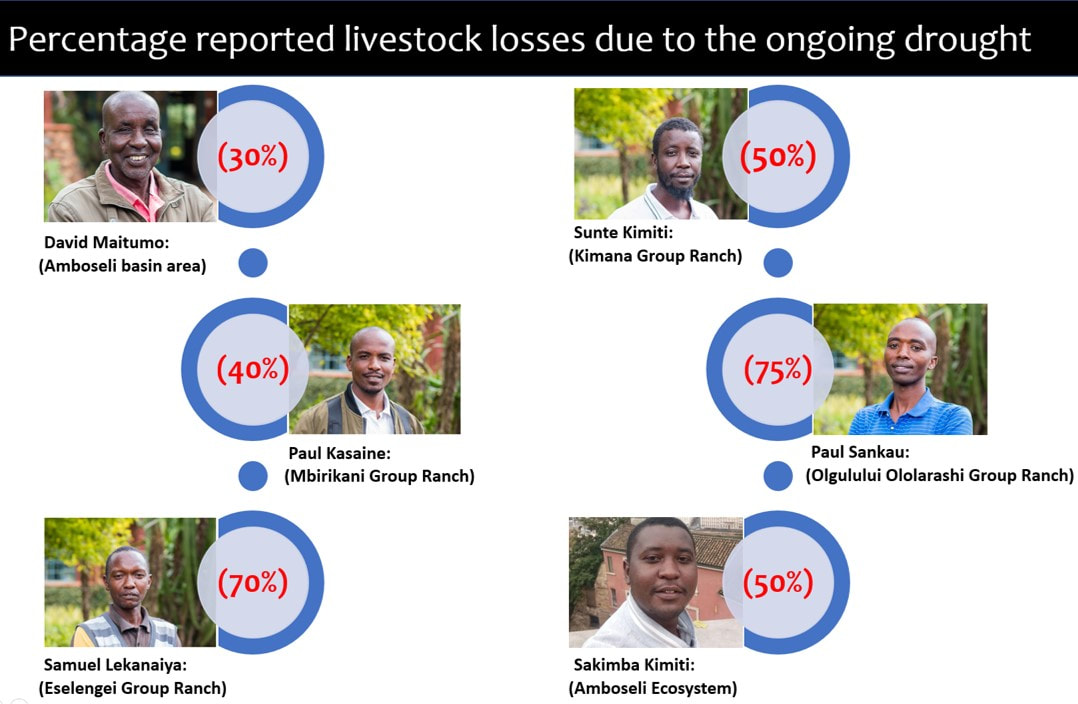

Many herders and crop farmers, based on my observations in Eselengei group ranch, have never experienced such a severe drought. To supplement the lack of grass, livestock are given commercial feeds and hay. A sack of flour meal costs between Ksh. 1600/= and Ksh. 3000/=, depending on quality. Following some rain, herds migrated to Magadi, Narok, Machakos, Kiboko, and our neighboring country, Tanzania; they are almost all returning to their permanent homesteads to feed the remaining livestock with commercial feeds.

Very few herds have lactating cows, and those that do, don’t sell their milk; instead, it is used for household purposes. Older calves are separated from their mothers as the drought bites on. The current livestock body condition ranges from 1-4 on a scale of 1-9, with 9 being the best. A mature animal cost around Ksh. 30,000, while sheep and goats’ cost Ksh. 4,000.

Many children have not attended school because their parents rely on rainfall to cultivate subsistence crops. Those in school are the children of parents who rely on irrigation and formal employment. Herders in Eselengei estimate that they have lost 70% of their livestock.

Sunte Kimiti:

The entire Amboseli ecosystem is experiencing a severe drought, which has resulted in the deaths of livestock and wildlife. As a result, pastoralists have been forced to migrate all over the region, some as far as Narok and the coastal lowlands.

Livestock are starving, prompting herders to look for areas where it has recently rained, such as the Chyulu Hills, Ukambani and Kibwezi. The cost of purchasing livestock feed and grass has been a financial burden for many people. Herders in Kimana who once had over 200 cows now have less than 80.

The dairy production from cattle has also been severely impacted, with a lack of pastures causing a decline in the livestock’s body condition. The market prices for livestock have decreased due to their condition and falling demand. The herders are struggling to pay for their children’s education. Some parents have been forced to withdraw their children from school due to a lack of fees.

Paul Kasaine:

Paul Sankau:

The pastoralists have had a difficult time. There hasn’t been any rain in three years. Only light showers have fallen during the months when rain is traditionally expected. As a result, there are few or no grasses in all areas. Reports from the OOGR indicate that some herders have lost close to 75% of their livestock. Wildlife has not been spared either. Many zebras, gazelles, giraffes, wildebeests, and even elephants have died as a result of the drought.

Since vegetation has disappeared and almost all grasslands now remain bare grounds, herders are buying crushed cones locally known as pumba, in addition to hay, and cone plants from farms under irrigation to feed our livestock. With all these efforts livestock are still dying. A double loss!

Following the light rain showers, herders have taken their livestock to the Chyulu hills, Oltepesi, Enkii, Oloile, Lemong’o, Olng’arua Loosinet, and Ngoirienito. The livestock body condition scores remain below average. Their prices continue to drop as children get back to school. The drought has also led to malnutrition in children as milk yields dry up.

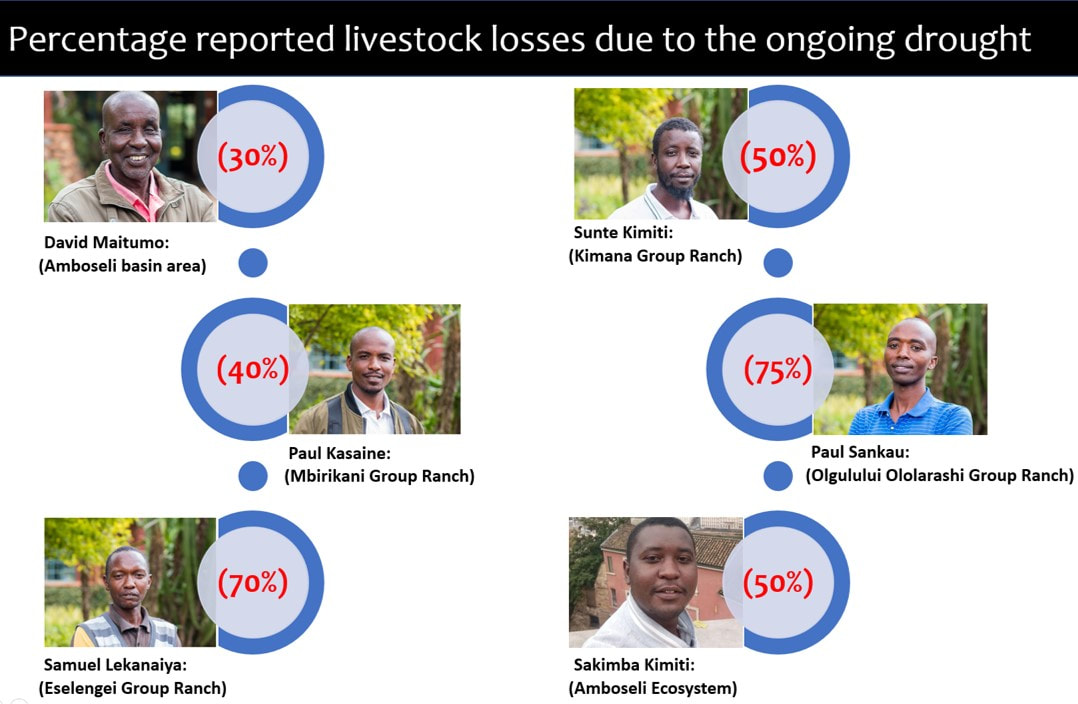

Many herders and crop farmers, based on my observations in Eselengei group ranch, have never experienced such a severe drought. To supplement the lack of grass, livestock are given commercial feeds and hay. A sack of flour meal costs between Ksh. 1600/= and Ksh. 3000/=, depending on quality. Following some rain, herds migrated to Magadi, Narok, Machakos, Kiboko, and our neighboring country, Tanzania; they are almost all returning to their permanent homesteads to feed the remaining livestock with commercial feeds.

Very few herds have lactating cows, and those that do, don’t sell their milk; instead, it is used for household purposes. Older calves are separated from their mothers as the drought bites on. The current livestock body condition ranges from 1-4 on a scale of 1-9, with 9 being the best. A mature animal cost around Ksh. 30,000, while sheep and goats’ cost Ksh. 4,000.

Many children have not attended school because their parents rely on rainfall to cultivate subsistence crops. Those in school are the children of parents who rely on irrigation and formal employment. Herders in Eselengei estimate that they have lost 70% of their livestock.

Sunte Kimiti:

The entire Amboseli ecosystem is experiencing a severe drought, which has resulted in the deaths of livestock and wildlife. As a result, pastoralists have been forced to migrate all over the region, some as far as Narok and the coastal lowlands.

Livestock are starving, prompting herders to look for areas where it has recently rained, such as the Chyulu Hills, Ukambani and Kibwezi. The cost of purchasing livestock feed and grass has been a financial burden for many people. Herders in Kimana who once had over 200 cows now have less than 80.

The dairy production from cattle has also been severely impacted, with a lack of pastures causing a decline in the livestock’s body condition. The market prices for livestock have decreased due to their condition and falling demand. The herders are struggling to pay for their children’s education. Some parents have been forced to withdraw their children from school due to a lack of fees.

Paul Kasaine:

Paul Sankau:

The pastoralists have had a difficult time. There hasn’t been any rain in three years. Only light showers have fallen during the months when rain is traditionally expected. As a result, there are few or no grasses in all areas. Reports from the OOGR indicate that some herders have lost close to 75% of their livestock. Wildlife has not been spared either. Many zebras, gazelles, giraffes, wildebeests, and even elephants have died as a result of the drought.

Since vegetation has disappeared and almost all grasslands now remain bare grounds, herders are buying crushed cones locally known as pumba, in addition to hay, and cone plants from farms under irrigation to feed our livestock. With all these efforts livestock are still dying. A double loss!

Following the light rain showers, herders have taken their livestock to the Chyulu hills, Oltepesi, Enkii, Oloile, Lemong’o, Olng’arua Loosinet, and Ngoirienito. The livestock body condition scores remain below average. Their prices continue to drop as children get back to school. The drought has also led to malnutrition in children as milk yields dry up.

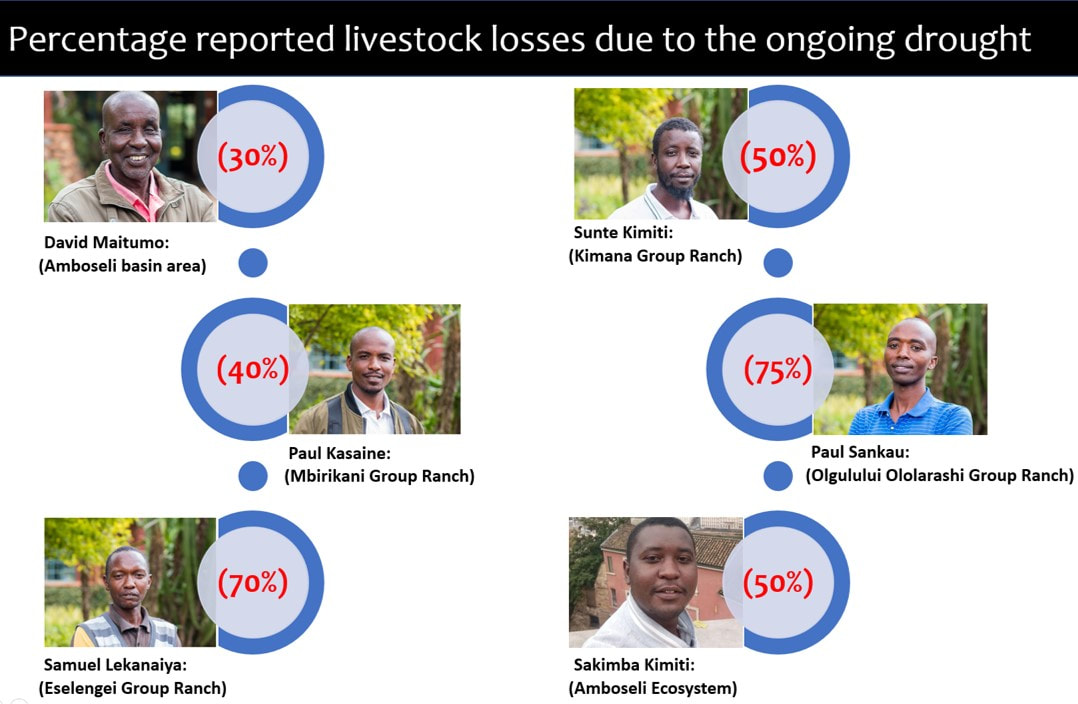

Many herders and crop farmers, based on my observations in Eselengei group ranch, have never experienced such a severe drought. To supplement the lack of grass, livestock are given commercial feeds and hay. A sack of flour meal costs between Ksh. 1600/= and Ksh. 3000/=, depending on quality. Following some rain, herds migrated to Magadi, Narok, Machakos, Kiboko, and our neighboring country, Tanzania; they are almost all returning to their permanent homesteads to feed the remaining livestock with commercial feeds.

Very few herds have lactating cows, and those that do, don’t sell their milk; instead, it is used for household purposes. Older calves are separated from their mothers as the drought bites on. The current livestock body condition ranges from 1-4 on a scale of 1-9, with 9 being the best. A mature animal cost around Ksh. 30,000, while sheep and goats’ cost Ksh. 4,000.

Many children have not attended school because their parents rely on rainfall to cultivate subsistence crops. Those in school are the children of parents who rely on irrigation and formal employment. Herders in Eselengei estimate that they have lost 70% of their livestock.

Sunte Kimiti:

The entire Amboseli ecosystem is experiencing a severe drought, which has resulted in the deaths of livestock and wildlife. As a result, pastoralists have been forced to migrate all over the region, some as far as Narok and the coastal lowlands.

Livestock are starving, prompting herders to look for areas where it has recently rained, such as the Chyulu Hills, Ukambani and Kibwezi. The cost of purchasing livestock feed and grass has been a financial burden for many people. Herders in Kimana who once had over 200 cows now have less than 80.

The dairy production from cattle has also been severely impacted, with a lack of pastures causing a decline in the livestock’s body condition. The market prices for livestock have decreased due to their condition and falling demand. The herders are struggling to pay for their children’s education. Some parents have been forced to withdraw their children from school due to a lack of fees.

Paul Kasaine:

Paul Sankau:

The pastoralists have had a difficult time. There hasn’t been any rain in three years. Only light showers have fallen during the months when rain is traditionally expected. As a result, there are few or no grasses in all areas. Reports from the OOGR indicate that some herders have lost close to 75% of their livestock. Wildlife has not been spared either. Many zebras, gazelles, giraffes, wildebeests, and even elephants have died as a result of the drought.

Since vegetation has disappeared and almost all grasslands now remain bare grounds, herders are buying crushed cones locally known as pumba, in addition to hay, and cone plants from farms under irrigation to feed our livestock. With all these efforts livestock are still dying. A double loss!

Following the light rain showers, herders have taken their livestock to the Chyulu hills, Oltepesi, Enkii, Oloile, Lemong’o, Olng’arua Loosinet, and Ngoirienito. The livestock body condition scores remain below average. Their prices continue to drop as children get back to school. The drought has also led to malnutrition in children as milk yields dry up.

For over 50 years, we’ve been pioneering conservation work in Amboseli sustained habitats, livelihoods and resilience through collaboration amid environmental changes, protecting biodiversity.

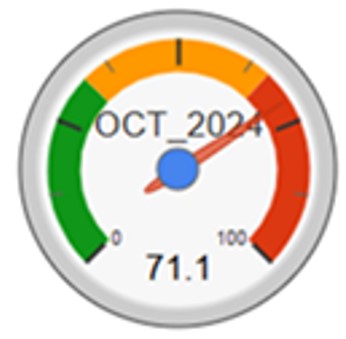

Current grazing pressure percentage.

Amboseli Conservation Program

P.O Box 15289-00509 or 62844-00200

Nairobi, Kenya.

Tel/Fax: +254 20 891360 / 891751

Email: acc@acc.or.ke

Amboseli Conservation Program

P.O Box 15289-00509 or 62844-00200

Nairobi, Kenya.

Tel/Fax: +254 20 891360 / 891751

Email: acc@acc.or.ke