During the Maasai cultural festival week of August 21st President Ruto announced that Amboseli National Park would be handed back to the management of the Kajiado County. The announcement was greeted with jubilation by Maasai leaders. The governor of Kajiado, Joseph Ole Lenku, welcomed the presidential directive, saying it corrected the historical injustice of Amboseli Game Reserve being seized from the county by presidential decree in 1974. Conservationist were caught unaware and many strongly oppose the declaration as a regressive move threatening the future of Amboseli’s world famous elephants and wildlife.

Having played a central role in the conservation of Amboseli since the 1960s, I have been asked from many quarters to comment on the handing back of Amboseli National Park to the Kajiado County and Maasai community. Let me start at the beginning to show why I support the move, and the conditions needed to ensure the future of Amboseli not only as a national park, but an ecosystem ten times the size of the park.

The first colonial administrators of the East African Protectorate fully recognized the pastoral communities in northern and southern Kenya as having conserved the richest wildlife lands on earth. Following the prohibition on sport hunting in both areas, a 10,696 square mile Southern Reserve was set aside in 1906 to protect wildlife in what would later become Kajiado District. Wildlife continued to thrive in the Southern Reserve under traditional Maasai land and husbandry management. Concerned over destruction of wildlife by colonial farmers and ranchers, the administration carved out Nairobi National Park from Maasailand in 1946, followed shortly after by Tsavo, Aberdare and Mt Kenya National Parks.

Efforts by the newly established autonomous Kenya National Parks authority to create national parks in Amboseli and Maasai Mara, the two richest wildlife areas in southern Kenya, were thwarted by Maasai resistance. Instead, a 1,269 square mile Amboseli National Reserve was established around Amboseli in 1948, administered by the Kenya National Park Trustees on behalf of the Kajiado County Council. In 1961 the national reserve was handed over to the Kajiado County Council to manage as the Amboseli Game Reserve. The Kajiado Council set aside a 30 square mile livestock free area around the Ol Tukai swamps to protect wildlife and foster tourism.

When I began my research in Amboseli in 1967, the warden Daniel Sindiyo, a Maasai himself, was seconded from the Game Department to administer the game reserve on behalf of the Kajiado County Council. We both

recognized the unique role the Maasai had played in conserving the wealth of wildlife in Amboseli and across southern Kenya. My research showed the pastoral way of life and the parallel seasonal migrations of livestock and wildlife across the 4,000 square kilometer ecosystem explained the wealth of Amboseli’s wildlife and its coexistence with the Maasai community.

By then pressures were mounting to create a national park around the Amboseli swamps, a move which would alienate the Maasai, deprive them of late season grazing and sever the wildlife migrations. We proposed instead an Amboseli Maasai Park which would ensure local participation in the benefits of wildlife and protect the integrity of the ecosystem.

Despite initially being accepted by the Kajiado County Council, the Maasai Park was ultimately rejected due to opposition politicians fueling suspicions of a government takeover. The Game Department pulled out and the county failed to invest in the conservation and management of Amboseli, leading to a rundown reserve, mounting conservation concerns and, in July 1974, President Jomo Kenyatta declaring Amboseli a National Park.

The Maasai considered the declaration illegal and showed their anger by spearing scores of elephants, lions and other wildlife. A compromise was reached after government was persuaded to cede the land and lodge revenues at Ol Tukai to the Kajiado County, pay the Maasai community a fee for supporting the wildlife migrations, and agreeing to future lodges being on community land to prevent overcrowding the park and earning the community direct tourism revenues.

Community-based conservation and an ecosystem approach to conserving wildlife was pioneered in Amboseli and adopted as national policy in 1977. In 2004 community leaders convened a meeting of conservation organizations, the Kenya Wildlife Service and county representatives to develop a ten-year ecosystem management plan. The plan, followed by an enlarged 2020-2030 plan, has seen wildlife numbers increase due to the deployment of some seven hundred community scouts, tourism enterprises, conservancies and the oversight of the Amboseli Ecosystem Trust constituted by the landowners and partners.

Having played a strong role in Amboseli’s community and ecosystem approach to wildlife conservation and promoted similar approaches nationally and internationally, I fully support the return of Amboseli to its traditional custodians. It does correct a historical injustice and vested wildlife in the community which has conserved it down the ages.

I do, however, caution the need to correct the injustice of Amboseli’s seizure through legal channels, not by presidential decree–as important as this is in setting the ball rolling. I took a similar position when President Kibaki decreed Amboseli be handed back to the Kajiado County Council in 2005. The decree led to an outcry, not only among conservationists, but also a Suswa Declaration by Maasai leaders rejecting the illegal declaration as an effort to buy Maasai votes. The Kibaki decree was halted by a court injunction, leading to angry tussles between government and Maasai leaders ever since.

The gazetting and degazetting of a national park must be done through the legal provisions of the Wildlife Act and the approval by the National Assembly. Amboseli could otherwise be taken back from the Maasai by a future presidential decree. The return to the Maasai should also be seen as the correction of an historical injustice, not an election gift. Other counties will otherwise press for a similar gift of national parks, and already are.

The handing back of Amboseli to the Maasai comes at a critical juncture. Frustrations are mounting among community members over rising conflict with wildlife and paltry revenues from the park. The frustrations, lack of returns from wildlife and the ongoing subdivision of the surrounding group ranches pose a grave threat to the future of the national park, migrations and ecosystem.

Under Maasai custodianship, Amboseli’s wildlife must find an enduring place in their future as it has in the past. The Kajiado County must also show it can manage Amboseli to the standards KWS has set. The county inherits a well-run park with regulations which have curbed the uncontrolled tourism crush harrying predators in many national reserves and sullying Kenya’s reputation as a premier wildlife destination.

The resumption of Amboseli management by the Kajiado County also offers an opportunity to secure the future of the ecosystem in the face of subdivision. With the County Assembly prepared to share a significant portion of the park revenues with the community, the payment for their ecological services could secure the ecosystem needed for wildlife migrations and the future of livestock herders. Conservation trust funds being set up by government and conservation organizations, along with payments for carbon and biodiversity credits and nature enterprises, could provide additional income to the Maasai community to keep their rangelands open.

With these caveats and the potential to secure the future of the entire ecosystem, I see a promising future for Amboseli National Park vested in the Maasai community. The government must and has given assurances that it will take bold steps to reform existing punitive wildlife policies to ensure our national parks are embedded within the ecosystems on which they depend, and embrace community engagement. The Parks Beyond Parks movement which I launched at KWS in 1997 has seen conservancies flourish and cover more land than all national parks and reserves combined. The combination of such community conservation efforts and national parks is a winning combination which augers well for conserving Kenya’s wealth of wildlife.

During the Maasai cultural festival week of August 21st President Ruto announced that Amboseli National Park would be handed back to the management of the Kajiado County. The announcement was greeted with jubilation by Maasai leaders. The governor of Kajiado, Joseph Ole Lenku, welcomed the presidential directive, saying it corrected the historical injustice of Amboseli Game Reserve being seized from the county by presidential decree in 1974. Conservationist were caught unaware and many strongly oppose the declaration as a regressive move threatening the future of Amboseli’s world famous elephants and wildlife.

Having played a central role in the conservation of Amboseli since the 1960s, I have been asked from many quarters to comment on the handing back of Amboseli National Park to the Kajiado County and Maasai community. Let me start at the beginning to show why I support the move, and the conditions needed to ensure the future of Amboseli not only as a national park, but an ecosystem ten times the size of the park.

The first colonial administrators of the East African Protectorate fully recognized the pastoral communities in northern and southern Kenya as having conserved the richest wildlife lands on earth. Following the prohibition on sport hunting in both areas, a 10,696 square mile Southern Reserve was set aside in 1906 to protect wildlife in what would later become Kajiado District. Wildlife continued to thrive in the Southern Reserve under traditional Maasai land and husbandry management. Concerned over destruction of wildlife by colonial farmers and ranchers, the administration carved out Nairobi National Park from Maasailand in 1946, followed shortly after by Tsavo, Aberdare and Mt Kenya National Parks.

Efforts by the newly established autonomous Kenya National Parks authority to create national parks in Amboseli and Maasai Mara, the two richest wildlife areas in southern Kenya, were thwarted by Maasai resistance. Instead, a 1,269 square mile Amboseli National Reserve was established around Amboseli in 1948, administered by the Kenya National Park Trustees on behalf of the Kajiado County Council. In 1961 the national reserve was handed over to the Kajiado County Council to manage as the Amboseli Game Reserve. The Kajiado Council set aside a 30 square mile livestock free area around the Ol Tukai swamps to protect wildlife and foster tourism.

When I began my research in Amboseli in 1967, the warden Daniel Sindiyo, a Maasai himself, was seconded from the Game Department to administer the game reserve on behalf of the Kajiado County Council. We both

recognized the unique role the Maasai had played in conserving the wealth of wildlife in Amboseli and across southern Kenya. My research showed the pastoral way of life and the parallel seasonal migrations of livestock and wildlife across the 4,000 square kilometer ecosystem explained the wealth of Amboseli’s wildlife and its coexistence with the Maasai community.

By then pressures were mounting to create a national park around the Amboseli swamps, a move which would alienate the Maasai, deprive them of late season grazing and sever the wildlife migrations. We proposed instead an Amboseli Maasai Park which would ensure local participation in the benefits of wildlife and protect the integrity of the ecosystem.

Despite initially being accepted by the Kajiado County Council, the Maasai Park was ultimately rejected due to opposition politicians fueling suspicions of a government takeover. The Game Department pulled out and the county failed to invest in the conservation and management of Amboseli, leading to a rundown reserve, mounting conservation concerns and, in July 1974, President Jomo Kenyatta declaring Amboseli a National Park.

The Maasai considered the declaration illegal and showed their anger by spearing scores of elephants, lions and other wildlife. A compromise was reached after government was persuaded to cede the land and lodge revenues at Ol Tukai to the Kajiado County, pay the Maasai community a fee for supporting the wildlife migrations, and agreeing to future lodges being on community land to prevent overcrowding the park and earning the community direct tourism revenues.

Community-based conservation and an ecosystem approach to conserving wildlife was pioneered in Amboseli and adopted as national policy in 1977. In 2004 community leaders convened a meeting of conservation organizations, the Kenya Wildlife Service and county representatives to develop a ten-year ecosystem management plan. The plan, followed by an enlarged 2020-2030 plan, has seen wildlife numbers increase due to the deployment of some seven hundred community scouts, tourism enterprises, conservancies and the oversight of the Amboseli Ecosystem Trust constituted by the landowners and partners.

Having played a strong role in Amboseli’s community and ecosystem approach to wildlife conservation and promoted similar approaches nationally and internationally, I fully support the return of Amboseli to its traditional custodians. It does correct a historical injustice and vested wildlife in the community which has conserved it down the ages.

I do, however, caution the need to correct the injustice of Amboseli’s seizure through legal channels, not by presidential decree–as important as this is in setting the ball rolling. I took a similar position when President Kibaki decreed Amboseli be handed back to the Kajiado County Council in 2005. The decree led to an outcry, not only among conservationists, but also a Suswa Declaration by Maasai leaders rejecting the illegal declaration as an effort to buy Maasai votes. The Kibaki decree was halted by a court injunction, leading to angry tussles between government and Maasai leaders ever since.

The gazetting and degazetting of a national park must be done through the legal provisions of the Wildlife Act and the approval by the National Assembly. Amboseli could otherwise be taken back from the Maasai by a future presidential decree. The return to the Maasai should also be seen as the correction of an historical injustice, not an election gift. Other counties will otherwise press for a similar gift of national parks, and already are.

The handing back of Amboseli to the Maasai comes at a critical juncture. Frustrations are mounting among community members over rising conflict with wildlife and paltry revenues from the park. The frustrations, lack of returns from wildlife and the ongoing subdivision of the surrounding group ranches pose a grave threat to the future of the national park, migrations and ecosystem.

Under Maasai custodianship, Amboseli’s wildlife must find an enduring place in their future as it has in the past. The Kajiado County must also show it can manage Amboseli to the standards KWS has set. The county inherits a well-run park with regulations which have curbed the uncontrolled tourism crush harrying predators in many national reserves and sullying Kenya’s reputation as a premier wildlife destination.

The resumption of Amboseli management by the Kajiado County also offers an opportunity to secure the future of the ecosystem in the face of subdivision. With the County Assembly prepared to share a significant portion of the park revenues with the community, the payment for their ecological services could secure the ecosystem needed for wildlife migrations and the future of livestock herders. Conservation trust funds being set up by government and conservation organizations, along with payments for carbon and biodiversity credits and nature enterprises, could provide additional income to the Maasai community to keep their rangelands open.

With these caveats and the potential to secure the future of the entire ecosystem, I see a promising future for Amboseli National Park vested in the Maasai community. The government must and has given assurances that it will take bold steps to reform existing punitive wildlife policies to ensure our national parks are embedded within the ecosystems on which they depend, and embrace community engagement. The Parks Beyond Parks movement which I launched at KWS in 1997 has seen conservancies flourish and cover more land than all national parks and reserves combined. The combination of such community conservation efforts and national parks is a winning combination which augers well for conserving Kenya’s wealth of wildlife.

During the Maasai cultural festival week of August 21st President Ruto announced that Amboseli National Park would be handed back to the management of the Kajiado County. The announcement was greeted with jubilation by Maasai leaders. The governor of Kajiado, Joseph Ole Lenku, welcomed the presidential directive, saying it corrected the historical injustice of Amboseli Game Reserve being seized from the county by presidential decree in 1974. Conservationist were caught unaware and many strongly oppose the declaration as a regressive move threatening the future of Amboseli’s world famous elephants and wildlife.

Having played a central role in the conservation of Amboseli since the 1960s, I have been asked from many quarters to comment on the handing back of Amboseli National Park to the Kajiado County and Maasai community. Let me start at the beginning to show why I support the move, and the conditions needed to ensure the future of Amboseli not only as a national park, but an ecosystem ten times the size of the park.

The first colonial administrators of the East African Protectorate fully recognized the pastoral communities in northern and southern Kenya as having conserved the richest wildlife lands on earth. Following the prohibition on sport hunting in both areas, a 10,696 square mile Southern Reserve was set aside in 1906 to protect wildlife in what would later become Kajiado District. Wildlife continued to thrive in the Southern Reserve under traditional Maasai land and husbandry management. Concerned over destruction of wildlife by colonial farmers and ranchers, the administration carved out Nairobi National Park from Maasailand in 1946, followed shortly after by Tsavo, Aberdare and Mt Kenya National Parks.

Efforts by the newly established autonomous Kenya National Parks authority to create national parks in Amboseli and Maasai Mara, the two richest wildlife areas in southern Kenya, were thwarted by Maasai resistance. Instead, a 1,269 square mile Amboseli National Reserve was established around Amboseli in 1948, administered by the Kenya National Park Trustees on behalf of the Kajiado County Council. In 1961 the national reserve was handed over to the Kajiado County Council to manage as the Amboseli Game Reserve. The Kajiado Council set aside a 30 square mile livestock free area around the Ol Tukai swamps to protect wildlife and foster tourism.

When I began my research in Amboseli in 1967, the warden Daniel Sindiyo, a Maasai himself, was seconded from the Game Department to administer the game reserve on behalf of the Kajiado County Council. We both

recognized the unique role the Maasai had played in conserving the wealth of wildlife in Amboseli and across southern Kenya. My research showed the pastoral way of life and the parallel seasonal migrations of livestock and wildlife across the 4,000 square kilometer ecosystem explained the wealth of Amboseli’s wildlife and its coexistence with the Maasai community.

By then pressures were mounting to create a national park around the Amboseli swamps, a move which would alienate the Maasai, deprive them of late season grazing and sever the wildlife migrations. We proposed instead an Amboseli Maasai Park which would ensure local participation in the benefits of wildlife and protect the integrity of the ecosystem.

Despite initially being accepted by the Kajiado County Council, the Maasai Park was ultimately rejected due to opposition politicians fueling suspicions of a government takeover. The Game Department pulled out and the county failed to invest in the conservation and management of Amboseli, leading to a rundown reserve, mounting conservation concerns and, in July 1974, President Jomo Kenyatta declaring Amboseli a National Park.

The Maasai considered the declaration illegal and showed their anger by spearing scores of elephants, lions and other wildlife. A compromise was reached after government was persuaded to cede the land and lodge revenues at Ol Tukai to the Kajiado County, pay the Maasai community a fee for supporting the wildlife migrations, and agreeing to future lodges being on community land to prevent overcrowding the park and earning the community direct tourism revenues.

Community-based conservation and an ecosystem approach to conserving wildlife was pioneered in Amboseli and adopted as national policy in 1977. In 2004 community leaders convened a meeting of conservation organizations, the Kenya Wildlife Service and county representatives to develop a ten-year ecosystem management plan. The plan, followed by an enlarged 2020-2030 plan, has seen wildlife numbers increase due to the deployment of some seven hundred community scouts, tourism enterprises, conservancies and the oversight of the Amboseli Ecosystem Trust constituted by the landowners and partners.

Having played a strong role in Amboseli’s community and ecosystem approach to wildlife conservation and promoted similar approaches nationally and internationally, I fully support the return of Amboseli to its traditional custodians. It does correct a historical injustice and vested wildlife in the community which has conserved it down the ages.

I do, however, caution the need to correct the injustice of Amboseli’s seizure through legal channels, not by presidential decree–as important as this is in setting the ball rolling. I took a similar position when President Kibaki decreed Amboseli be handed back to the Kajiado County Council in 2005. The decree led to an outcry, not only among conservationists, but also a Suswa Declaration by Maasai leaders rejecting the illegal declaration as an effort to buy Maasai votes. The Kibaki decree was halted by a court injunction, leading to angry tussles between government and Maasai leaders ever since.

The gazetting and degazetting of a national park must be done through the legal provisions of the Wildlife Act and the approval by the National Assembly. Amboseli could otherwise be taken back from the Maasai by a future presidential decree. The return to the Maasai should also be seen as the correction of an historical injustice, not an election gift. Other counties will otherwise press for a similar gift of national parks, and already are.

The handing back of Amboseli to the Maasai comes at a critical juncture. Frustrations are mounting among community members over rising conflict with wildlife and paltry revenues from the park. The frustrations, lack of returns from wildlife and the ongoing subdivision of the surrounding group ranches pose a grave threat to the future of the national park, migrations and ecosystem.

Under Maasai custodianship, Amboseli’s wildlife must find an enduring place in their future as it has in the past. The Kajiado County must also show it can manage Amboseli to the standards KWS has set. The county inherits a well-run park with regulations which have curbed the uncontrolled tourism crush harrying predators in many national reserves and sullying Kenya’s reputation as a premier wildlife destination.

The resumption of Amboseli management by the Kajiado County also offers an opportunity to secure the future of the ecosystem in the face of subdivision. With the County Assembly prepared to share a significant portion of the park revenues with the community, the payment for their ecological services could secure the ecosystem needed for wildlife migrations and the future of livestock herders. Conservation trust funds being set up by government and conservation organizations, along with payments for carbon and biodiversity credits and nature enterprises, could provide additional income to the Maasai community to keep their rangelands open.

With these caveats and the potential to secure the future of the entire ecosystem, I see a promising future for Amboseli National Park vested in the Maasai community. The government must and has given assurances that it will take bold steps to reform existing punitive wildlife policies to ensure our national parks are embedded within the ecosystems on which they depend, and embrace community engagement. The Parks Beyond Parks movement which I launched at KWS in 1997 has seen conservancies flourish and cover more land than all national parks and reserves combined. The combination of such community conservation efforts and national parks is a winning combination which augers well for conserving Kenya’s wealth of wildlife.

During the Maasai cultural festival week of August 21st President Ruto announced that Amboseli National Park would be handed back to the management of the Kajiado County. The announcement was greeted with jubilation by Maasai leaders. The governor of Kajiado, Joseph Ole Lenku, welcomed the presidential directive, saying it corrected the historical injustice of Amboseli Game Reserve being seized from the county by presidential decree in 1974. Conservationist were caught unaware and many strongly oppose the declaration as a regressive move threatening the future of Amboseli’s world famous elephants and wildlife.

Having played a central role in the conservation of Amboseli since the 1960s, I have been asked from many quarters to comment on the handing back of Amboseli National Park to the Kajiado County and Maasai community. Let me start at the beginning to show why I support the move, and the conditions needed to ensure the future of Amboseli not only as a national park, but an ecosystem ten times the size of the park.

The first colonial administrators of the East African Protectorate fully recognized the pastoral communities in northern and southern Kenya as having conserved the richest wildlife lands on earth. Following the prohibition on sport hunting in both areas, a 10,696 square mile Southern Reserve was set aside in 1906 to protect wildlife in what would later become Kajiado District. Wildlife continued to thrive in the Southern Reserve under traditional Maasai land and husbandry management. Concerned over destruction of wildlife by colonial farmers and ranchers, the administration carved out Nairobi National Park from Maasailand in 1946, followed shortly after by Tsavo, Aberdare and Mt Kenya National Parks.

Efforts by the newly established autonomous Kenya National Parks authority to create national parks in Amboseli and Maasai Mara, the two richest wildlife areas in southern Kenya, were thwarted by Maasai resistance. Instead, a 1,269 square mile Amboseli National Reserve was established around Amboseli in 1948, administered by the Kenya National Park Trustees on behalf of the Kajiado County Council. In 1961 the national reserve was handed over to the Kajiado County Council to manage as the Amboseli Game Reserve. The Kajiado Council set aside a 30 square mile livestock free area around the Ol Tukai swamps to protect wildlife and foster tourism.

When I began my research in Amboseli in 1967, the warden Daniel Sindiyo, a Maasai himself, was seconded from the Game Department to administer the game reserve on behalf of the Kajiado County Council. We both

recognized the unique role the Maasai had played in conserving the wealth of wildlife in Amboseli and across southern Kenya. My research showed the pastoral way of life and the parallel seasonal migrations of livestock and wildlife across the 4,000 square kilometer ecosystem explained the wealth of Amboseli’s wildlife and its coexistence with the Maasai community.

By then pressures were mounting to create a national park around the Amboseli swamps, a move which would alienate the Maasai, deprive them of late season grazing and sever the wildlife migrations. We proposed instead an Amboseli Maasai Park which would ensure local participation in the benefits of wildlife and protect the integrity of the ecosystem.

Despite initially being accepted by the Kajiado County Council, the Maasai Park was ultimately rejected due to opposition politicians fueling suspicions of a government takeover. The Game Department pulled out and the county failed to invest in the conservation and management of Amboseli, leading to a rundown reserve, mounting conservation concerns and, in July 1974, President Jomo Kenyatta declaring Amboseli a National Park.

The Maasai considered the declaration illegal and showed their anger by spearing scores of elephants, lions and other wildlife. A compromise was reached after government was persuaded to cede the land and lodge revenues at Ol Tukai to the Kajiado County, pay the Maasai community a fee for supporting the wildlife migrations, and agreeing to future lodges being on community land to prevent overcrowding the park and earning the community direct tourism revenues.

Community-based conservation and an ecosystem approach to conserving wildlife was pioneered in Amboseli and adopted as national policy in 1977. In 2004 community leaders convened a meeting of conservation organizations, the Kenya Wildlife Service and county representatives to develop a ten-year ecosystem management plan. The plan, followed by an enlarged 2020-2030 plan, has seen wildlife numbers increase due to the deployment of some seven hundred community scouts, tourism enterprises, conservancies and the oversight of the Amboseli Ecosystem Trust constituted by the landowners and partners.

Having played a strong role in Amboseli’s community and ecosystem approach to wildlife conservation and promoted similar approaches nationally and internationally, I fully support the return of Amboseli to its traditional custodians. It does correct a historical injustice and vested wildlife in the community which has conserved it down the ages.

I do, however, caution the need to correct the injustice of Amboseli’s seizure through legal channels, not by presidential decree–as important as this is in setting the ball rolling. I took a similar position when President Kibaki decreed Amboseli be handed back to the Kajiado County Council in 2005. The decree led to an outcry, not only among conservationists, but also a Suswa Declaration by Maasai leaders rejecting the illegal declaration as an effort to buy Maasai votes. The Kibaki decree was halted by a court injunction, leading to angry tussles between government and Maasai leaders ever since.

The gazetting and degazetting of a national park must be done through the legal provisions of the Wildlife Act and the approval by the National Assembly. Amboseli could otherwise be taken back from the Maasai by a future presidential decree. The return to the Maasai should also be seen as the correction of an historical injustice, not an election gift. Other counties will otherwise press for a similar gift of national parks, and already are.

The handing back of Amboseli to the Maasai comes at a critical juncture. Frustrations are mounting among community members over rising conflict with wildlife and paltry revenues from the park. The frustrations, lack of returns from wildlife and the ongoing subdivision of the surrounding group ranches pose a grave threat to the future of the national park, migrations and ecosystem.

Under Maasai custodianship, Amboseli’s wildlife must find an enduring place in their future as it has in the past. The Kajiado County must also show it can manage Amboseli to the standards KWS has set. The county inherits a well-run park with regulations which have curbed the uncontrolled tourism crush harrying predators in many national reserves and sullying Kenya’s reputation as a premier wildlife destination.

The resumption of Amboseli management by the Kajiado County also offers an opportunity to secure the future of the ecosystem in the face of subdivision. With the County Assembly prepared to share a significant portion of the park revenues with the community, the payment for their ecological services could secure the ecosystem needed for wildlife migrations and the future of livestock herders. Conservation trust funds being set up by government and conservation organizations, along with payments for carbon and biodiversity credits and nature enterprises, could provide additional income to the Maasai community to keep their rangelands open.

With these caveats and the potential to secure the future of the entire ecosystem, I see a promising future for Amboseli National Park vested in the Maasai community. The government must and has given assurances that it will take bold steps to reform existing punitive wildlife policies to ensure our national parks are embedded within the ecosystems on which they depend, and embrace community engagement. The Parks Beyond Parks movement which I launched at KWS in 1997 has seen conservancies flourish and cover more land than all national parks and reserves combined. The combination of such community conservation efforts and national parks is a winning combination which augers well for conserving Kenya’s wealth of wildlife.

For over 50 years, we’ve been pioneering conservation work in Amboseli sustained habitats, livelihoods and resilience through collaboration amid environmental changes, protecting biodiversity.

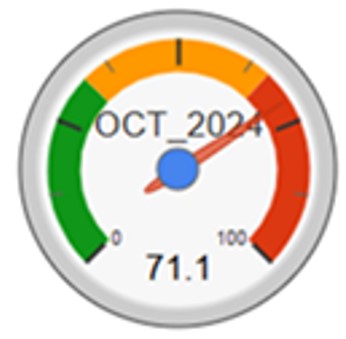

Current grazing pressure percentage.

Amboseli Conservation Program

P.O Box 15289-00509 or 62844-00200

Nairobi, Kenya.

Tel/Fax: +254 20 891360 / 891751

Email: acc@acc.or.ke

Amboseli Conservation Program

P.O Box 15289-00509 or 62844-00200

Nairobi, Kenya.

Tel/Fax: +254 20 891360 / 891751

Email: acc@acc.or.ke