Over 30,000 elephants were poached across Africa in 2013, driven by the sky-rocketing price of ivory and illegal trafficking. Kenya was cited by the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species as a major conduit for the export of ivory. Over the last year Kenya Wildlife Service has been lambasted in the press and by watchdog conservation bodies for covering up a poaching crisis in Kenya. KWS countered that poaching fell in 2014: poaching is under control following a concerted effort by government forces. At the urging of ACP in the Ministry of the Environment, KWS convened a National Elephant Conference on 19th and 20th February to take stock of the status of elephants.

A summary of the continental picture by the African Elephant Specialist Group showed that poaching posed a grave threat to the species, especially in West, Central Africa and much of Eastern Africa. In contrast, elephant populations remained stable in Southern Africa. Kenya showed a decrease in poaching in 2014. The findings were supported by detailed locational analysis by KWS and Iain Douglas-Hamilton of Save the Elephants. The number of poached elephants as a proportion of all animals dying fell below critical levels in most populations, with the notable exception of Maasai Mara.

Though the decline in poaching is good news, the status of Kenya’s elephants overall is clouded by uncertainties over numbers in forested parks, including Abedares and Mount Kenya. Forest parks, which account for twenty percent or more of the Kenya’s elephant population, have not been counted in years.

The best news came from Amboseli. Here poaching levels remain negligible—only one for certain, perhaps three in 2014, all on the periphery of their range. Numbers have reached 1,500 and are still growing after recovering 2009 drought losses. The population is also expanding its range, making Amboseli one of the safest locations in eastern and central Africa.

Amboseli’s success in protecting elephants stems in large measure from the engagement of the Maasai community in conservation dating back to the mid-1970s. At the KWS conference David Western reviewed the history of the Amboseli elephant population based on his long-term monitoring work starting in 1967. He showed that ivory poaching killed off half the elephants in less than five years in the early 1970s. Poaching stopped abruptly once the community began benefiting from parks revenues, this despite the continuing losses to poachers throughout Kenya until the world-wide ivory ban of 1990. By then, the Amboseli elephants had recovered to their pre-poaching levels.

The recent success of elephant conservation in Amboseli is due to KWS field forces, organizations such as Big Life, Amboseli Trust, ACC and other NGOs funding the network of some 300 community scouts, and the backing of the Maasai community. The lessons from Amboseli and need for a broad collaborative approach to conserving elephants in the Kenya-Tanzania borderlands was presented at the Kenya National Elephant Workshop at Kenya Wildlife Service, Nairobi.

Over 30,000 elephants were poached across Africa in 2013, driven by the sky-rocketing price of ivory and illegal trafficking. Kenya was cited by the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species as a major conduit for the export of ivory. Over the last year Kenya Wildlife Service has been lambasted in the press and by watchdog conservation bodies for covering up a poaching crisis in Kenya. KWS countered that poaching fell in 2014: poaching is under control following a concerted effort by government forces. At the urging of ACP in the Ministry of the Environment, KWS convened a National Elephant Conference on 19th and 20th February to take stock of the status of elephants.

A summary of the continental picture by the African Elephant Specialist Group showed that poaching posed a grave threat to the species, especially in West, Central Africa and much of Eastern Africa. In contrast, elephant populations remained stable in Southern Africa. Kenya showed a decrease in poaching in 2014. The findings were supported by detailed locational analysis by KWS and Iain Douglas-Hamilton of Save the Elephants. The number of poached elephants as a proportion of all animals dying fell below critical levels in most populations, with the notable exception of Maasai Mara.

Though the decline in poaching is good news, the status of Kenya’s elephants overall is clouded by uncertainties over numbers in forested parks, including Abedares and Mount Kenya. Forest parks, which account for twenty percent or more of the Kenya’s elephant population, have not been counted in years.

The best news came from Amboseli. Here poaching levels remain negligible—only one for certain, perhaps three in 2014, all on the periphery of their range. Numbers have reached 1,500 and are still growing after recovering 2009 drought losses. The population is also expanding its range, making Amboseli one of the safest locations in eastern and central Africa.

Amboseli’s success in protecting elephants stems in large measure from the engagement of the Maasai community in conservation dating back to the mid-1970s. At the KWS conference David Western reviewed the history of the Amboseli elephant population based on his long-term monitoring work starting in 1967. He showed that ivory poaching killed off half the elephants in less than five years in the early 1970s. Poaching stopped abruptly once the community began benefiting from parks revenues, this despite the continuing losses to poachers throughout Kenya until the world-wide ivory ban of 1990. By then, the Amboseli elephants had recovered to their pre-poaching levels.

The recent success of elephant conservation in Amboseli is due to KWS field forces, organizations such as Big Life, Amboseli Trust, ACC and other NGOs funding the network of some 300 community scouts, and the backing of the Maasai community. The lessons from Amboseli and need for a broad collaborative approach to conserving elephants in the Kenya-Tanzania borderlands was presented at the Kenya National Elephant Workshop at Kenya Wildlife Service, Nairobi.

Over 30,000 elephants were poached across Africa in 2013, driven by the sky-rocketing price of ivory and illegal trafficking. Kenya was cited by the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species as a major conduit for the export of ivory. Over the last year Kenya Wildlife Service has been lambasted in the press and by watchdog conservation bodies for covering up a poaching crisis in Kenya. KWS countered that poaching fell in 2014: poaching is under control following a concerted effort by government forces. At the urging of ACP in the Ministry of the Environment, KWS convened a National Elephant Conference on 19th and 20th February to take stock of the status of elephants.

A summary of the continental picture by the African Elephant Specialist Group showed that poaching posed a grave threat to the species, especially in West, Central Africa and much of Eastern Africa. In contrast, elephant populations remained stable in Southern Africa. Kenya showed a decrease in poaching in 2014. The findings were supported by detailed locational analysis by KWS and Iain Douglas-Hamilton of Save the Elephants. The number of poached elephants as a proportion of all animals dying fell below critical levels in most populations, with the notable exception of Maasai Mara.

Though the decline in poaching is good news, the status of Kenya’s elephants overall is clouded by uncertainties over numbers in forested parks, including Abedares and Mount Kenya. Forest parks, which account for twenty percent or more of the Kenya’s elephant population, have not been counted in years.

The best news came from Amboseli. Here poaching levels remain negligible—only one for certain, perhaps three in 2014, all on the periphery of their range. Numbers have reached 1,500 and are still growing after recovering 2009 drought losses. The population is also expanding its range, making Amboseli one of the safest locations in eastern and central Africa.

Amboseli’s success in protecting elephants stems in large measure from the engagement of the Maasai community in conservation dating back to the mid-1970s. At the KWS conference David Western reviewed the history of the Amboseli elephant population based on his long-term monitoring work starting in 1967. He showed that ivory poaching killed off half the elephants in less than five years in the early 1970s. Poaching stopped abruptly once the community began benefiting from parks revenues, this despite the continuing losses to poachers throughout Kenya until the world-wide ivory ban of 1990. By then, the Amboseli elephants had recovered to their pre-poaching levels.

The recent success of elephant conservation in Amboseli is due to KWS field forces, organizations such as Big Life, Amboseli Trust, ACC and other NGOs funding the network of some 300 community scouts, and the backing of the Maasai community. The lessons from Amboseli and need for a broad collaborative approach to conserving elephants in the Kenya-Tanzania borderlands was presented at the Kenya National Elephant Workshop at Kenya Wildlife Service, Nairobi.

Over 30,000 elephants were poached across Africa in 2013, driven by the sky-rocketing price of ivory and illegal trafficking. Kenya was cited by the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species as a major conduit for the export of ivory. Over the last year Kenya Wildlife Service has been lambasted in the press and by watchdog conservation bodies for covering up a poaching crisis in Kenya. KWS countered that poaching fell in 2014: poaching is under control following a concerted effort by government forces. At the urging of ACP in the Ministry of the Environment, KWS convened a National Elephant Conference on 19th and 20th February to take stock of the status of elephants.

A summary of the continental picture by the African Elephant Specialist Group showed that poaching posed a grave threat to the species, especially in West, Central Africa and much of Eastern Africa. In contrast, elephant populations remained stable in Southern Africa. Kenya showed a decrease in poaching in 2014. The findings were supported by detailed locational analysis by KWS and Iain Douglas-Hamilton of Save the Elephants. The number of poached elephants as a proportion of all animals dying fell below critical levels in most populations, with the notable exception of Maasai Mara.

Though the decline in poaching is good news, the status of Kenya’s elephants overall is clouded by uncertainties over numbers in forested parks, including Abedares and Mount Kenya. Forest parks, which account for twenty percent or more of the Kenya’s elephant population, have not been counted in years.

The best news came from Amboseli. Here poaching levels remain negligible—only one for certain, perhaps three in 2014, all on the periphery of their range. Numbers have reached 1,500 and are still growing after recovering 2009 drought losses. The population is also expanding its range, making Amboseli one of the safest locations in eastern and central Africa.

Amboseli’s success in protecting elephants stems in large measure from the engagement of the Maasai community in conservation dating back to the mid-1970s. At the KWS conference David Western reviewed the history of the Amboseli elephant population based on his long-term monitoring work starting in 1967. He showed that ivory poaching killed off half the elephants in less than five years in the early 1970s. Poaching stopped abruptly once the community began benefiting from parks revenues, this despite the continuing losses to poachers throughout Kenya until the world-wide ivory ban of 1990. By then, the Amboseli elephants had recovered to their pre-poaching levels.

The recent success of elephant conservation in Amboseli is due to KWS field forces, organizations such as Big Life, Amboseli Trust, ACC and other NGOs funding the network of some 300 community scouts, and the backing of the Maasai community. The lessons from Amboseli and need for a broad collaborative approach to conserving elephants in the Kenya-Tanzania borderlands was presented at the Kenya National Elephant Workshop at Kenya Wildlife Service, Nairobi.

For over 50 years, we’ve been pioneering conservation work in Amboseli sustained habitats, livelihoods and resilience through collaboration amid environmental changes, protecting biodiversity.

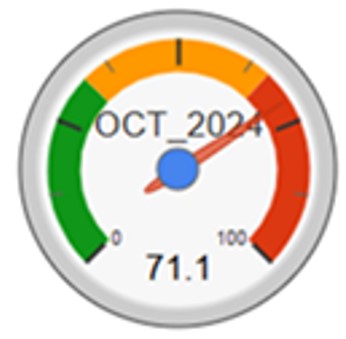

Current grazing pressure percentage.

Amboseli Conservation Program

P.O Box 15289-00509 or 62844-00200

Nairobi, Kenya.

Tel/Fax: +254 20 891360 / 891751

Email: acc@acc.or.ke

Amboseli Conservation Program

P.O Box 15289-00509 or 62844-00200

Nairobi, Kenya.

Tel/Fax: +254 20 891360 / 891751

Email: acc@acc.or.ke