Prince William’s presentation of the 2020 Tusk Award to Kenya’s John Kamanga gives global recognition to an African leader of community-based conservation (CBC). Above all, the award celebrates John’s outstanding stewardship of the South Rift Association of Landowners (Soralo) which has overseen a resurgence of wildlife in the Kenya-Tanzania borderlands.

I joined John at the award ceremony in Nairobi, transmitted by video from the Kensington Place in London on December 3rd 2020. The tension among John’s family and colleagues erupted into a joyful outburst when Prince Willian declared John this year’s winner of the prestigious Tusk Award. John asked me to say a few words in his honor, as his “conservation mentor,” he said. I lamented ironically how long it had taken the international community to recognize the remarkable legacy of the Maasai in conserving the richest wildlife lands on earth. Finally, here was John being honored on the world stage for his leadership in rekindling the capacity of his community to coexist with wildlife before those skills are lost forever.

Nairobi’s Covid-19 curfew put, paid to my longer reflections on John’s journey from Maasai pastoralist to national and global conservationist—and the far longer road community-based conservation has taken from its roots in southern Kenya to a global movement. Let me add here the words I would have given in John’s honor as a CBC leader, Covid-19 permitting.

The first tentative step in recognizing the role of communities in conserving Kenya’s wildlife heritage was taken in Amboseli in the late 1960s when I worked with the warden, Daniel Sindiyo to advocate a Maasai wildlife park. A presidential decree declaring Amboseli National Park scuttled the endeavor but provoked such a spate of wildlife killings that the government agreed to pay the surrounding Maasai community for migratory wildlife using its land, and to promote ecotourism enterprises to reap the economic benefits and fund social amenities such as schools and health clinics. That small victory, backed by a Tourism and Wildlife loan from the World Bank, prompted Kenya to introduce a new wildlife policy promoting community participation in wildlife conservation.

Similar community conservation efforts sprang up in Zimbabwe and Namibia, and with gathering speed, around the world as the limitations of parks were recognized and the prospects of conserving wildlife on the extensive community lands took root.

Recognizing a watershed moment, the Liz Claiborne Art Ortenberg Foundation (LCAOF) convened a meeting of community leaders, conservation organizations and donors at Airlie House in Virginia in 1994. The novel assembly collated case studies from around the world to give visibility and backing to the emerging CBC movement, dedicated to the coexistence of wildlife and community livelihoods. The success of the Airlie House event prompted similar gatherings at a Red Lodge meeting in Montana to promote collaborative resource management across the Interior West of the U.S, and communities across East Africa convened by the African Conservation Centre (ACC) to foster local conservation initiatives.

The Kenya Wildlife Service (KWS) gave the CBC movement a big shot in the arm in setting up the Community Wildlife Service and granting seed money to promising community programs. In 1997, I launched the KWS’ Parks Beyond Parks program to recognize and encourage the emerging CBC movement, pushed for legal registration of community organizations, and set up the National Wildlife Forum to give them a strong voice. The European Union sponsored the Biodiversity Conservation Program and Tourism Trust Fund which gave start-up grants to dozens of local initiatives, including the first community sanctuary in Kimana, ecotourist lodges, tourism infrastructure and community scouts trained by KWS. The first community owned lodge, Ilng’wesi, backed by the Lewa Wildlife Conservancy and funded by KWS and LCAOF, laid the foundation of a host of community ecotourism ventures to follow.

Each new step and innovation triggered yet others, creating the self-propelling momentum behind the success of locally-inspired movements. By the early 2000s dozens of new community-based efforts had sprung up, among them the Northern Rangelands Trust in northern Kenya, and the Taita-Taveta, Mara, Amboseli and SORALO initiatives in southern Kenya, each spawning dozens of new conservancies.

Ecotourism Kenya, launched by ACC to promote green tourism, refreshed Kenya’s fading reputation as Africa’s premier safari destination by promoting conservancies and injecting tourism revenues into the CBC movement. The ecotourism boost and the formation of the Kenya Wildlife Conservancy Association has given the CBC movement a strong foundation. In the last decade, over 150 conservancies have spread across Kenya covering more land than all Kenya’s national parks and reserves and employing more wildlife rangers than KWS.

Which brings me back to SORALO, among the most successful of all Parks beyond Parks in Kenya. ACC started the ball rolling in the South Rift by helping Shompole Group Ranch set up an ecotourism lodge and conservation programs. John Kamanga, chairman of Olkiramatian Group Ranch, invited John Waithaka, director of ACC and me to meet his committee and support the plans they had drawn up to emulate Shomopole’s success–and to go further in engaging the community. John’s plans married well with ACC‘s vision of creating a conservation link between Amboseli and Maasai Mara to conserve the richest assemblage of vertebrates in all Africa and find space for the growing elephant herds spreading out from the two parks.

The success of Shompole and Olkiramatian soon drew in other group ranches, and so SORALO was born. Before long, the growing network of group ranch conservation plans fulfilled the vison of linking Mara and Amboseli across the Rift Valley. Key to the growth of SORALO has been John’s leadership and ACC’s support of Maasai traditional practices for managing pastures, the health of the land and fostering coexistence with wildlife. Among the many innovations is the construction of the Lale’enok Centre which deploys local resource assessors to monitor the rangelands and community rangers to protect wildlife and regulate the use of pastures; the promotion of cultural tourism; encouraging women’s enterprises; attracting visiting scientists and university field visits; setting up an education outreach program and launching a Rebuilding the Pride predator program to restore carnivore populations. The unique feature of the Lale’enok Centre is its practice of using Maasai traditional methods of producing, sharing, and using knowledge for the common good of the community.

The CBC initiatives in SORALO, Amboseli and across southern Kenya in collaboration with ACC and other conservation organizations have created “horizontal learning exchanges,” the swapping of ideas and skills among communities within Kenya and reciprocal visits across Africa, with American ranchers and among pastoral communities around the world, The Rangelands Association of Kenya, cattlemen’s associations and the Maasai Heritage Program are some of the new bodies to have sprung up from the learning exchanges, many of them with John at the helm.

There is no leader without a successful movement and no movement without effective leaders. The CBC movement in Kenya has spawned and been driven by several world class conservation leaders, John among them. Growing up as a livestock herder with wildlife as his neighbors, John is the epitome of and an ambassador for the coexistence of people and wildlife. SORALO over the last two decades has seen its lion population grow four-fold, elephants return to the South Rift after decades of being driven out by poachers, other wildlife thrive and the community take pride in its conservation achievements.

The Tusk Award gives long overdue recognition to John’s conservation achievements through SORALO and on the national and international stage. For the most part the success of CBC in Kenya has succeeded because of the traditional land practices of its pastoral peoples and their ability to live with wildlife. With those traditions eroding, the land shrinking and being carved up by private allotments, CBC now calls for new forms of collective action and land management–if the pastoral herds no less than wildlife are to find a place in the East African future savannas. This new landscape calls for visionary leaders like John Kamanga, strong community organizations and the support of national and international conservation organizations dedicating to supporting them.

Prince William’s presentation of the 2020 Tusk Award to Kenya’s John Kamanga gives global recognition to an African leader of community-based conservation (CBC). Above all, the award celebrates John’s outstanding stewardship of the South Rift Association of Landowners (Soralo) which has overseen a resurgence of wildlife in the Kenya-Tanzania borderlands.

I joined John at the award ceremony in Nairobi, transmitted by video from the Kensington Place in London on December 3rd 2020. The tension among John’s family and colleagues erupted into a joyful outburst when Prince Willian declared John this year’s winner of the prestigious Tusk Award. John asked me to say a few words in his honor, as his “conservation mentor,” he said. I lamented ironically how long it had taken the international community to recognize the remarkable legacy of the Maasai in conserving the richest wildlife lands on earth. Finally, here was John being honored on the world stage for his leadership in rekindling the capacity of his community to coexist with wildlife before those skills are lost forever.

Nairobi’s Covid-19 curfew put, paid to my longer reflections on John’s journey from Maasai pastoralist to national and global conservationist—and the far longer road community-based conservation has taken from its roots in southern Kenya to a global movement. Let me add here the words I would have given in John’s honor as a CBC leader, Covid-19 permitting.

The first tentative step in recognizing the role of communities in conserving Kenya’s wildlife heritage was taken in Amboseli in the late 1960s when I worked with the warden, Daniel Sindiyo to advocate a Maasai wildlife park. A presidential decree declaring Amboseli National Park scuttled the endeavor but provoked such a spate of wildlife killings that the government agreed to pay the surrounding Maasai community for migratory wildlife using its land, and to promote ecotourism enterprises to reap the economic benefits and fund social amenities such as schools and health clinics. That small victory, backed by a Tourism and Wildlife loan from the World Bank, prompted Kenya to introduce a new wildlife policy promoting community participation in wildlife conservation.

Similar community conservation efforts sprang up in Zimbabwe and Namibia, and with gathering speed, around the world as the limitations of parks were recognized and the prospects of conserving wildlife on the extensive community lands took root.

Recognizing a watershed moment, the Liz Claiborne Art Ortenberg Foundation (LCAOF) convened a meeting of community leaders, conservation organizations and donors at Airlie House in Virginia in 1994. The novel assembly collated case studies from around the world to give visibility and backing to the emerging CBC movement, dedicated to the coexistence of wildlife and community livelihoods. The success of the Airlie House event prompted similar gatherings at a Red Lodge meeting in Montana to promote collaborative resource management across the Interior West of the U.S, and communities across East Africa convened by the African Conservation Centre (ACC) to foster local conservation initiatives.

The Kenya Wildlife Service (KWS) gave the CBC movement a big shot in the arm in setting up the Community Wildlife Service and granting seed money to promising community programs. In 1997, I launched the KWS’ Parks Beyond Parks program to recognize and encourage the emerging CBC movement, pushed for legal registration of community organizations, and set up the National Wildlife Forum to give them a strong voice. The European Union sponsored the Biodiversity Conservation Program and Tourism Trust Fund which gave start-up grants to dozens of local initiatives, including the first community sanctuary in Kimana, ecotourist lodges, tourism infrastructure and community scouts trained by KWS. The first community owned lodge, Ilng’wesi, backed by the Lewa Wildlife Conservancy and funded by KWS and LCAOF, laid the foundation of a host of community ecotourism ventures to follow.

Each new step and innovation triggered yet others, creating the self-propelling momentum behind the success of locally-inspired movements. By the early 2000s dozens of new community-based efforts had sprung up, among them the Northern Rangelands Trust in northern Kenya, and the Taita-Taveta, Mara, Amboseli and SORALO initiatives in southern Kenya, each spawning dozens of new conservancies.

Ecotourism Kenya, launched by ACC to promote green tourism, refreshed Kenya’s fading reputation as Africa’s premier safari destination by promoting conservancies and injecting tourism revenues into the CBC movement. The ecotourism boost and the formation of the Kenya Wildlife Conservancy Association has given the CBC movement a strong foundation. In the last decade, over 150 conservancies have spread across Kenya covering more land than all Kenya’s national parks and reserves and employing more wildlife rangers than KWS.

Which brings me back to SORALO, among the most successful of all Parks beyond Parks in Kenya. ACC started the ball rolling in the South Rift by helping Shompole Group Ranch set up an ecotourism lodge and conservation programs. John Kamanga, chairman of Olkiramatian Group Ranch, invited John Waithaka, director of ACC and me to meet his committee and support the plans they had drawn up to emulate Shomopole’s success–and to go further in engaging the community. John’s plans married well with ACC‘s vision of creating a conservation link between Amboseli and Maasai Mara to conserve the richest assemblage of vertebrates in all Africa and find space for the growing elephant herds spreading out from the two parks.

The success of Shompole and Olkiramatian soon drew in other group ranches, and so SORALO was born. Before long, the growing network of group ranch conservation plans fulfilled the vison of linking Mara and Amboseli across the Rift Valley. Key to the growth of SORALO has been John’s leadership and ACC’s support of Maasai traditional practices for managing pastures, the health of the land and fostering coexistence with wildlife. Among the many innovations is the construction of the Lale’enok Centre which deploys local resource assessors to monitor the rangelands and community rangers to protect wildlife and regulate the use of pastures; the promotion of cultural tourism; encouraging women’s enterprises; attracting visiting scientists and university field visits; setting up an education outreach program and launching a Rebuilding the Pride predator program to restore carnivore populations. The unique feature of the Lale’enok Centre is its practice of using Maasai traditional methods of producing, sharing, and using knowledge for the common good of the community.

The CBC initiatives in SORALO, Amboseli and across southern Kenya in collaboration with ACC and other conservation organizations have created “horizontal learning exchanges,” the swapping of ideas and skills among communities within Kenya and reciprocal visits across Africa, with American ranchers and among pastoral communities around the world, The Rangelands Association of Kenya, cattlemen’s associations and the Maasai Heritage Program are some of the new bodies to have sprung up from the learning exchanges, many of them with John at the helm.

There is no leader without a successful movement and no movement without effective leaders. The CBC movement in Kenya has spawned and been driven by several world class conservation leaders, John among them. Growing up as a livestock herder with wildlife as his neighbors, John is the epitome of and an ambassador for the coexistence of people and wildlife. SORALO over the last two decades has seen its lion population grow four-fold, elephants return to the South Rift after decades of being driven out by poachers, other wildlife thrive and the community take pride in its conservation achievements.

The Tusk Award gives long overdue recognition to John’s conservation achievements through SORALO and on the national and international stage. For the most part the success of CBC in Kenya has succeeded because of the traditional land practices of its pastoral peoples and their ability to live with wildlife. With those traditions eroding, the land shrinking and being carved up by private allotments, CBC now calls for new forms of collective action and land management–if the pastoral herds no less than wildlife are to find a place in the East African future savannas. This new landscape calls for visionary leaders like John Kamanga, strong community organizations and the support of national and international conservation organizations dedicating to supporting them.

Prince William’s presentation of the 2020 Tusk Award to Kenya’s John Kamanga gives global recognition to an African leader of community-based conservation (CBC). Above all, the award celebrates John’s outstanding stewardship of the South Rift Association of Landowners (Soralo) which has overseen a resurgence of wildlife in the Kenya-Tanzania borderlands.

I joined John at the award ceremony in Nairobi, transmitted by video from the Kensington Place in London on December 3rd 2020. The tension among John’s family and colleagues erupted into a joyful outburst when Prince Willian declared John this year’s winner of the prestigious Tusk Award. John asked me to say a few words in his honor, as his “conservation mentor,” he said. I lamented ironically how long it had taken the international community to recognize the remarkable legacy of the Maasai in conserving the richest wildlife lands on earth. Finally, here was John being honored on the world stage for his leadership in rekindling the capacity of his community to coexist with wildlife before those skills are lost forever.

Nairobi’s Covid-19 curfew put, paid to my longer reflections on John’s journey from Maasai pastoralist to national and global conservationist—and the far longer road community-based conservation has taken from its roots in southern Kenya to a global movement. Let me add here the words I would have given in John’s honor as a CBC leader, Covid-19 permitting.

The first tentative step in recognizing the role of communities in conserving Kenya’s wildlife heritage was taken in Amboseli in the late 1960s when I worked with the warden, Daniel Sindiyo to advocate a Maasai wildlife park. A presidential decree declaring Amboseli National Park scuttled the endeavor but provoked such a spate of wildlife killings that the government agreed to pay the surrounding Maasai community for migratory wildlife using its land, and to promote ecotourism enterprises to reap the economic benefits and fund social amenities such as schools and health clinics. That small victory, backed by a Tourism and Wildlife loan from the World Bank, prompted Kenya to introduce a new wildlife policy promoting community participation in wildlife conservation.

Similar community conservation efforts sprang up in Zimbabwe and Namibia, and with gathering speed, around the world as the limitations of parks were recognized and the prospects of conserving wildlife on the extensive community lands took root.

Recognizing a watershed moment, the Liz Claiborne Art Ortenberg Foundation (LCAOF) convened a meeting of community leaders, conservation organizations and donors at Airlie House in Virginia in 1994. The novel assembly collated case studies from around the world to give visibility and backing to the emerging CBC movement, dedicated to the coexistence of wildlife and community livelihoods. The success of the Airlie House event prompted similar gatherings at a Red Lodge meeting in Montana to promote collaborative resource management across the Interior West of the U.S, and communities across East Africa convened by the African Conservation Centre (ACC) to foster local conservation initiatives.

The Kenya Wildlife Service (KWS) gave the CBC movement a big shot in the arm in setting up the Community Wildlife Service and granting seed money to promising community programs. In 1997, I launched the KWS’ Parks Beyond Parks program to recognize and encourage the emerging CBC movement, pushed for legal registration of community organizations, and set up the National Wildlife Forum to give them a strong voice. The European Union sponsored the Biodiversity Conservation Program and Tourism Trust Fund which gave start-up grants to dozens of local initiatives, including the first community sanctuary in Kimana, ecotourist lodges, tourism infrastructure and community scouts trained by KWS. The first community owned lodge, Ilng’wesi, backed by the Lewa Wildlife Conservancy and funded by KWS and LCAOF, laid the foundation of a host of community ecotourism ventures to follow.

Each new step and innovation triggered yet others, creating the self-propelling momentum behind the success of locally-inspired movements. By the early 2000s dozens of new community-based efforts had sprung up, among them the Northern Rangelands Trust in northern Kenya, and the Taita-Taveta, Mara, Amboseli and SORALO initiatives in southern Kenya, each spawning dozens of new conservancies.

Ecotourism Kenya, launched by ACC to promote green tourism, refreshed Kenya’s fading reputation as Africa’s premier safari destination by promoting conservancies and injecting tourism revenues into the CBC movement. The ecotourism boost and the formation of the Kenya Wildlife Conservancy Association has given the CBC movement a strong foundation. In the last decade, over 150 conservancies have spread across Kenya covering more land than all Kenya’s national parks and reserves and employing more wildlife rangers than KWS.

Which brings me back to SORALO, among the most successful of all Parks beyond Parks in Kenya. ACC started the ball rolling in the South Rift by helping Shompole Group Ranch set up an ecotourism lodge and conservation programs. John Kamanga, chairman of Olkiramatian Group Ranch, invited John Waithaka, director of ACC and me to meet his committee and support the plans they had drawn up to emulate Shomopole’s success–and to go further in engaging the community. John’s plans married well with ACC‘s vision of creating a conservation link between Amboseli and Maasai Mara to conserve the richest assemblage of vertebrates in all Africa and find space for the growing elephant herds spreading out from the two parks.

The success of Shompole and Olkiramatian soon drew in other group ranches, and so SORALO was born. Before long, the growing network of group ranch conservation plans fulfilled the vison of linking Mara and Amboseli across the Rift Valley. Key to the growth of SORALO has been John’s leadership and ACC’s support of Maasai traditional practices for managing pastures, the health of the land and fostering coexistence with wildlife. Among the many innovations is the construction of the Lale’enok Centre which deploys local resource assessors to monitor the rangelands and community rangers to protect wildlife and regulate the use of pastures; the promotion of cultural tourism; encouraging women’s enterprises; attracting visiting scientists and university field visits; setting up an education outreach program and launching a Rebuilding the Pride predator program to restore carnivore populations. The unique feature of the Lale’enok Centre is its practice of using Maasai traditional methods of producing, sharing, and using knowledge for the common good of the community.

The CBC initiatives in SORALO, Amboseli and across southern Kenya in collaboration with ACC and other conservation organizations have created “horizontal learning exchanges,” the swapping of ideas and skills among communities within Kenya and reciprocal visits across Africa, with American ranchers and among pastoral communities around the world, The Rangelands Association of Kenya, cattlemen’s associations and the Maasai Heritage Program are some of the new bodies to have sprung up from the learning exchanges, many of them with John at the helm.

There is no leader without a successful movement and no movement without effective leaders. The CBC movement in Kenya has spawned and been driven by several world class conservation leaders, John among them. Growing up as a livestock herder with wildlife as his neighbors, John is the epitome of and an ambassador for the coexistence of people and wildlife. SORALO over the last two decades has seen its lion population grow four-fold, elephants return to the South Rift after decades of being driven out by poachers, other wildlife thrive and the community take pride in its conservation achievements.

The Tusk Award gives long overdue recognition to John’s conservation achievements through SORALO and on the national and international stage. For the most part the success of CBC in Kenya has succeeded because of the traditional land practices of its pastoral peoples and their ability to live with wildlife. With those traditions eroding, the land shrinking and being carved up by private allotments, CBC now calls for new forms of collective action and land management–if the pastoral herds no less than wildlife are to find a place in the East African future savannas. This new landscape calls for visionary leaders like John Kamanga, strong community organizations and the support of national and international conservation organizations dedicating to supporting them.

Prince William’s presentation of the 2020 Tusk Award to Kenya’s John Kamanga gives global recognition to an African leader of community-based conservation (CBC). Above all, the award celebrates John’s outstanding stewardship of the South Rift Association of Landowners (Soralo) which has overseen a resurgence of wildlife in the Kenya-Tanzania borderlands.

I joined John at the award ceremony in Nairobi, transmitted by video from the Kensington Place in London on December 3rd 2020. The tension among John’s family and colleagues erupted into a joyful outburst when Prince Willian declared John this year’s winner of the prestigious Tusk Award. John asked me to say a few words in his honor, as his “conservation mentor,” he said. I lamented ironically how long it had taken the international community to recognize the remarkable legacy of the Maasai in conserving the richest wildlife lands on earth. Finally, here was John being honored on the world stage for his leadership in rekindling the capacity of his community to coexist with wildlife before those skills are lost forever.

Nairobi’s Covid-19 curfew put, paid to my longer reflections on John’s journey from Maasai pastoralist to national and global conservationist—and the far longer road community-based conservation has taken from its roots in southern Kenya to a global movement. Let me add here the words I would have given in John’s honor as a CBC leader, Covid-19 permitting.

The first tentative step in recognizing the role of communities in conserving Kenya’s wildlife heritage was taken in Amboseli in the late 1960s when I worked with the warden, Daniel Sindiyo to advocate a Maasai wildlife park. A presidential decree declaring Amboseli National Park scuttled the endeavor but provoked such a spate of wildlife killings that the government agreed to pay the surrounding Maasai community for migratory wildlife using its land, and to promote ecotourism enterprises to reap the economic benefits and fund social amenities such as schools and health clinics. That small victory, backed by a Tourism and Wildlife loan from the World Bank, prompted Kenya to introduce a new wildlife policy promoting community participation in wildlife conservation.

Similar community conservation efforts sprang up in Zimbabwe and Namibia, and with gathering speed, around the world as the limitations of parks were recognized and the prospects of conserving wildlife on the extensive community lands took root.

Recognizing a watershed moment, the Liz Claiborne Art Ortenberg Foundation (LCAOF) convened a meeting of community leaders, conservation organizations and donors at Airlie House in Virginia in 1994. The novel assembly collated case studies from around the world to give visibility and backing to the emerging CBC movement, dedicated to the coexistence of wildlife and community livelihoods. The success of the Airlie House event prompted similar gatherings at a Red Lodge meeting in Montana to promote collaborative resource management across the Interior West of the U.S, and communities across East Africa convened by the African Conservation Centre (ACC) to foster local conservation initiatives.

The Kenya Wildlife Service (KWS) gave the CBC movement a big shot in the arm in setting up the Community Wildlife Service and granting seed money to promising community programs. In 1997, I launched the KWS’ Parks Beyond Parks program to recognize and encourage the emerging CBC movement, pushed for legal registration of community organizations, and set up the National Wildlife Forum to give them a strong voice. The European Union sponsored the Biodiversity Conservation Program and Tourism Trust Fund which gave start-up grants to dozens of local initiatives, including the first community sanctuary in Kimana, ecotourist lodges, tourism infrastructure and community scouts trained by KWS. The first community owned lodge, Ilng’wesi, backed by the Lewa Wildlife Conservancy and funded by KWS and LCAOF, laid the foundation of a host of community ecotourism ventures to follow.

Each new step and innovation triggered yet others, creating the self-propelling momentum behind the success of locally-inspired movements. By the early 2000s dozens of new community-based efforts had sprung up, among them the Northern Rangelands Trust in northern Kenya, and the Taita-Taveta, Mara, Amboseli and SORALO initiatives in southern Kenya, each spawning dozens of new conservancies.

Ecotourism Kenya, launched by ACC to promote green tourism, refreshed Kenya’s fading reputation as Africa’s premier safari destination by promoting conservancies and injecting tourism revenues into the CBC movement. The ecotourism boost and the formation of the Kenya Wildlife Conservancy Association has given the CBC movement a strong foundation. In the last decade, over 150 conservancies have spread across Kenya covering more land than all Kenya’s national parks and reserves and employing more wildlife rangers than KWS.

Which brings me back to SORALO, among the most successful of all Parks beyond Parks in Kenya. ACC started the ball rolling in the South Rift by helping Shompole Group Ranch set up an ecotourism lodge and conservation programs. John Kamanga, chairman of Olkiramatian Group Ranch, invited John Waithaka, director of ACC and me to meet his committee and support the plans they had drawn up to emulate Shomopole’s success–and to go further in engaging the community. John’s plans married well with ACC‘s vision of creating a conservation link between Amboseli and Maasai Mara to conserve the richest assemblage of vertebrates in all Africa and find space for the growing elephant herds spreading out from the two parks.

The success of Shompole and Olkiramatian soon drew in other group ranches, and so SORALO was born. Before long, the growing network of group ranch conservation plans fulfilled the vison of linking Mara and Amboseli across the Rift Valley. Key to the growth of SORALO has been John’s leadership and ACC’s support of Maasai traditional practices for managing pastures, the health of the land and fostering coexistence with wildlife. Among the many innovations is the construction of the Lale’enok Centre which deploys local resource assessors to monitor the rangelands and community rangers to protect wildlife and regulate the use of pastures; the promotion of cultural tourism; encouraging women’s enterprises; attracting visiting scientists and university field visits; setting up an education outreach program and launching a Rebuilding the Pride predator program to restore carnivore populations. The unique feature of the Lale’enok Centre is its practice of using Maasai traditional methods of producing, sharing, and using knowledge for the common good of the community.

The CBC initiatives in SORALO, Amboseli and across southern Kenya in collaboration with ACC and other conservation organizations have created “horizontal learning exchanges,” the swapping of ideas and skills among communities within Kenya and reciprocal visits across Africa, with American ranchers and among pastoral communities around the world, The Rangelands Association of Kenya, cattlemen’s associations and the Maasai Heritage Program are some of the new bodies to have sprung up from the learning exchanges, many of them with John at the helm.

There is no leader without a successful movement and no movement without effective leaders. The CBC movement in Kenya has spawned and been driven by several world class conservation leaders, John among them. Growing up as a livestock herder with wildlife as his neighbors, John is the epitome of and an ambassador for the coexistence of people and wildlife. SORALO over the last two decades has seen its lion population grow four-fold, elephants return to the South Rift after decades of being driven out by poachers, other wildlife thrive and the community take pride in its conservation achievements.

The Tusk Award gives long overdue recognition to John’s conservation achievements through SORALO and on the national and international stage. For the most part the success of CBC in Kenya has succeeded because of the traditional land practices of its pastoral peoples and their ability to live with wildlife. With those traditions eroding, the land shrinking and being carved up by private allotments, CBC now calls for new forms of collective action and land management–if the pastoral herds no less than wildlife are to find a place in the East African future savannas. This new landscape calls for visionary leaders like John Kamanga, strong community organizations and the support of national and international conservation organizations dedicating to supporting them.

For over 50 years, we’ve been pioneering conservation work in Amboseli sustained habitats, livelihoods and resilience through collaboration amid environmental changes, protecting biodiversity.

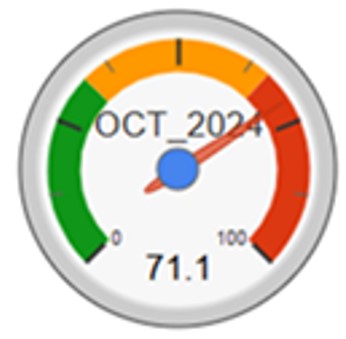

Current grazing pressure percentage.

Amboseli Conservation Program

P.O Box 15289-00509 or 62844-00200

Nairobi, Kenya.

Tel/Fax: +254 20 891360 / 891751

Email: acc@acc.or.ke

Amboseli Conservation Program

P.O Box 15289-00509 or 62844-00200

Nairobi, Kenya.

Tel/Fax: +254 20 891360 / 891751

Email: acc@acc.or.ke