The rains finally fell heavily in Amboseli on November 17th, flooding the basin in a seven-hour deluge. I had to fly through low cloud and a steady downpour to land at the main strip. On the ground the pans had filled with water and the wildebeest had vacated the swamps and gathered on the short grass plains. Two days later most wildebeest had migrated north. I have not seen such a dramatic start to the rains in years. The previous week, the plains were sere and windswept, a few days later puddled with water and sprouting new growth.

Kenya’s Met office had been predicting the imminent onset of torrential El Niño rains since September and the government has raised emergency funds in preparation for the expected floods. The hard times in Amboseli, which I reported in October ACP news, continued into mid-November. By the time the rains came Maasai cattle were dying and over 7,000 had pushed into the park for forage. I reported that wildlife would get by because of the unexpected spread of the swamps and proliferation of new growth. Despite the delayed rains, adults wildebeest are generally in fair condition, having got a boost from the extensive grass growth at the far end of Longinye Swamp.

The newly weaning calves are in far worse condition though. A few have hides turned white and staring with starvation, similar to the wildebeest dying in the 2009 drought. Their poor condition and dying livestock point to the depleted state of Amboseli pastures. And, once again, the buffalo area grazing deep in the swamp for lack of pasture. I photograph a herd of 87 buffalo grazing up to their bellies in the swamps with infants barely keeping above water.

The pressure on Amboseli speaks to the far bigger threat of rangeland degradation in Eastern Africa and the rising frequency of drought (download article here). However good the El Niño rains, the recovery of the rangeland will be sharply depressed by heavy grazing. The carryover effect spells hard times for pastoralist and their livestock and growing conflict with wildlife.

The rains finally fell heavily in Amboseli on November 17th, flooding the basin in a seven-hour deluge. I had to fly through low cloud and a steady downpour to land at the main strip. On the ground the pans had filled with water and the wildebeest had vacated the swamps and gathered on the short grass plains. Two days later most wildebeest had migrated north. I have not seen such a dramatic start to the rains in years. The previous week, the plains were sere and windswept, a few days later puddled with water and sprouting new growth.

Kenya’s Met office had been predicting the imminent onset of torrential El Niño rains since September and the government has raised emergency funds in preparation for the expected floods. The hard times in Amboseli, which I reported in October ACP news, continued into mid-November. By the time the rains came Maasai cattle were dying and over 7,000 had pushed into the park for forage. I reported that wildlife would get by because of the unexpected spread of the swamps and proliferation of new growth. Despite the delayed rains, adults wildebeest are generally in fair condition, having got a boost from the extensive grass growth at the far end of Longinye Swamp.

The newly weaning calves are in far worse condition though. A few have hides turned white and staring with starvation, similar to the wildebeest dying in the 2009 drought. Their poor condition and dying livestock point to the depleted state of Amboseli pastures. And, once again, the buffalo area grazing deep in the swamp for lack of pasture. I photograph a herd of 87 buffalo grazing up to their bellies in the swamps with infants barely keeping above water.

The pressure on Amboseli speaks to the far bigger threat of rangeland degradation in Eastern Africa and the rising frequency of drought (download article here). However good the El Niño rains, the recovery of the rangeland will be sharply depressed by heavy grazing. The carryover effect spells hard times for pastoralist and their livestock and growing conflict with wildlife.

The rains finally fell heavily in Amboseli on November 17th, flooding the basin in a seven-hour deluge. I had to fly through low cloud and a steady downpour to land at the main strip. On the ground the pans had filled with water and the wildebeest had vacated the swamps and gathered on the short grass plains. Two days later most wildebeest had migrated north. I have not seen such a dramatic start to the rains in years. The previous week, the plains were sere and windswept, a few days later puddled with water and sprouting new growth.

Kenya’s Met office had been predicting the imminent onset of torrential El Niño rains since September and the government has raised emergency funds in preparation for the expected floods. The hard times in Amboseli, which I reported in October ACP news, continued into mid-November. By the time the rains came Maasai cattle were dying and over 7,000 had pushed into the park for forage. I reported that wildlife would get by because of the unexpected spread of the swamps and proliferation of new growth. Despite the delayed rains, adults wildebeest are generally in fair condition, having got a boost from the extensive grass growth at the far end of Longinye Swamp.

The newly weaning calves are in far worse condition though. A few have hides turned white and staring with starvation, similar to the wildebeest dying in the 2009 drought. Their poor condition and dying livestock point to the depleted state of Amboseli pastures. And, once again, the buffalo area grazing deep in the swamp for lack of pasture. I photograph a herd of 87 buffalo grazing up to their bellies in the swamps with infants barely keeping above water.

The pressure on Amboseli speaks to the far bigger threat of rangeland degradation in Eastern Africa and the rising frequency of drought (download article here). However good the El Niño rains, the recovery of the rangeland will be sharply depressed by heavy grazing. The carryover effect spells hard times for pastoralist and their livestock and growing conflict with wildlife.

The rains finally fell heavily in Amboseli on November 17th, flooding the basin in a seven-hour deluge. I had to fly through low cloud and a steady downpour to land at the main strip. On the ground the pans had filled with water and the wildebeest had vacated the swamps and gathered on the short grass plains. Two days later most wildebeest had migrated north. I have not seen such a dramatic start to the rains in years. The previous week, the plains were sere and windswept, a few days later puddled with water and sprouting new growth.

Kenya’s Met office had been predicting the imminent onset of torrential El Niño rains since September and the government has raised emergency funds in preparation for the expected floods. The hard times in Amboseli, which I reported in October ACP news, continued into mid-November. By the time the rains came Maasai cattle were dying and over 7,000 had pushed into the park for forage. I reported that wildlife would get by because of the unexpected spread of the swamps and proliferation of new growth. Despite the delayed rains, adults wildebeest are generally in fair condition, having got a boost from the extensive grass growth at the far end of Longinye Swamp.

The newly weaning calves are in far worse condition though. A few have hides turned white and staring with starvation, similar to the wildebeest dying in the 2009 drought. Their poor condition and dying livestock point to the depleted state of Amboseli pastures. And, once again, the buffalo area grazing deep in the swamp for lack of pasture. I photograph a herd of 87 buffalo grazing up to their bellies in the swamps with infants barely keeping above water.

The pressure on Amboseli speaks to the far bigger threat of rangeland degradation in Eastern Africa and the rising frequency of drought (download article here). However good the El Niño rains, the recovery of the rangeland will be sharply depressed by heavy grazing. The carryover effect spells hard times for pastoralist and their livestock and growing conflict with wildlife.

For over 50 years, we’ve been pioneering conservation work in Amboseli sustained habitats, livelihoods and resilience through collaboration amid environmental changes, protecting biodiversity.

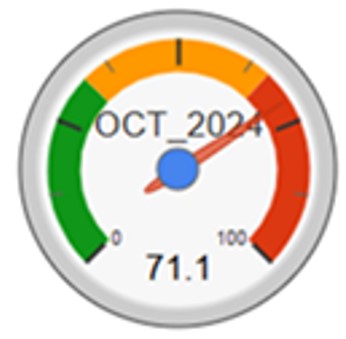

Current grazing pressure percentage.

Amboseli Conservation Program

P.O Box 15289-00509 or 62844-00200

Nairobi, Kenya.

Tel/Fax: +254 20 891360 / 891751

Email: acc@acc.or.ke

Amboseli Conservation Program

P.O Box 15289-00509 or 62844-00200

Nairobi, Kenya.

Tel/Fax: +254 20 891360 / 891751

Email: acc@acc.or.ke