The pandemic is already disrupting every sector of society, from entertainment and sports to manufacturing and the health and service industries. And the worst is yet to come. Conservationists blame the pandemic on the loss of biodiversity degraded ecosystems and climate change. They have a point. New virulent diseases, along with invasive species and pests, thrive when nature dies.

In the case of the Coronavirus the blame lies squarely on the illegal trade in wildlife species, fueled by globalization. Diseases such as Ebola, Marburg and HIV erupted in small scattered communities in the past but remained localized epidemics. No longer.

In the last few decades, global travel has spawned virulent novel viruses such as SARS, MERS, H1N1 and COVID-19, infecting hundreds of millions around the world in weeks. These new pandemics are a grave threat to every nation, every individual. causing 6 of 10 infectious diseases, 2.5 billion illnesses and 2.7 million deaths each year.

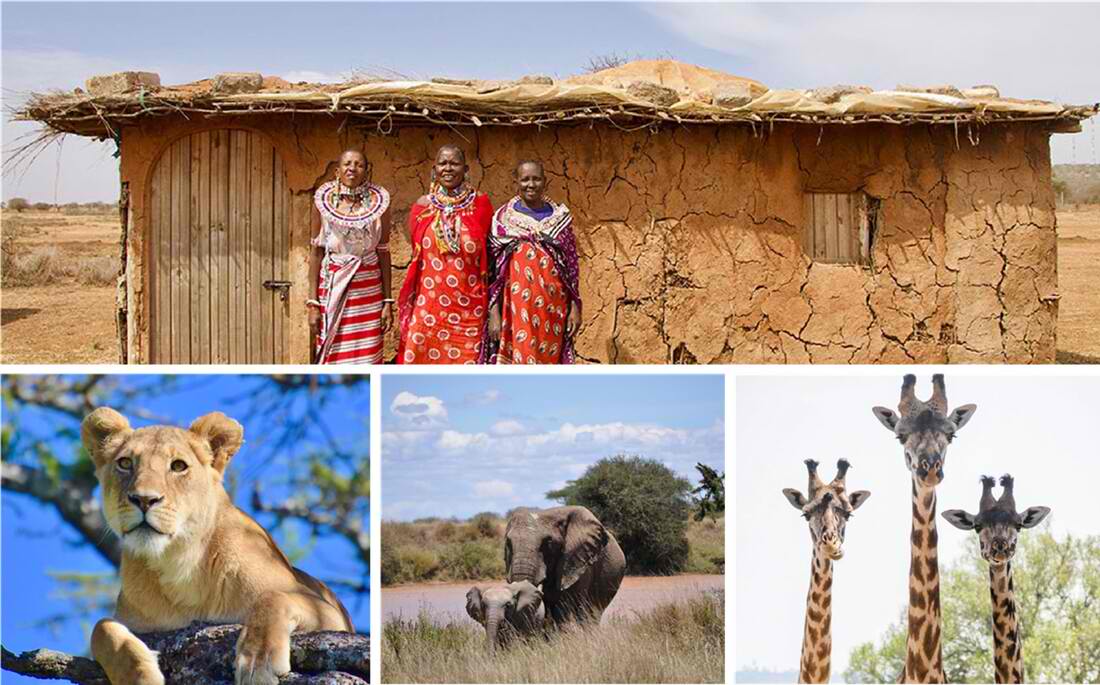

The wildlife trade, worth $23 billion annually, operates largely underground like drug trafficking. And like the ivory wars which slashed elephant numbers across Africa from 1.2 million in 1970 to 450,000 today, the wildlife trade is driven by rising wealth in Asia. Hundreds of species of amphibians, snakes, fish, birds and mammals are butchered for the wildlife trade, among them bats, civets and pangolins suspected of transmitting lethal viruses.

We can’t be sure which species in the wildlife market in Wuhan sparked the COVID-19 pandemic. Regardless, the cramped confined conditions flouting concerns for animal welfare and human health, have unleashed the most devastating pandemic in modern times.

The COVID-19 pandemic has been dubbed the revenge of wildlife. Revenge it isn’t. Coronavirus smites indiscriminately. For every illegal trader infected, hundreds of millions of people are at risk, among them ardent animal lovers, doctors and nurses. Overlooked is the impact of the pandemic on wildlife.

First, lobby your politicians to pressure for the closure of the wildlife trade. A remote shot two years ago, China and other Asian countries have since banned the sale of ivory, showing a total closure is possible. Elephant poaching has declined sharply across Africa since the bans. Now is the moment to press for an end to the animal trade and make the world a safer place.

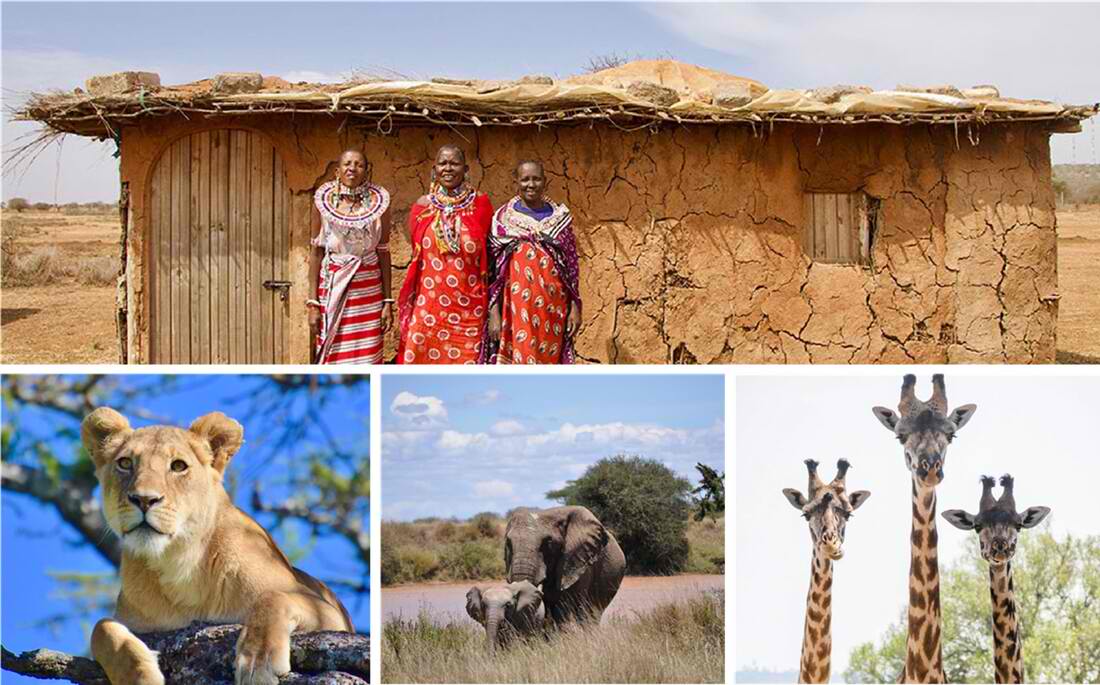

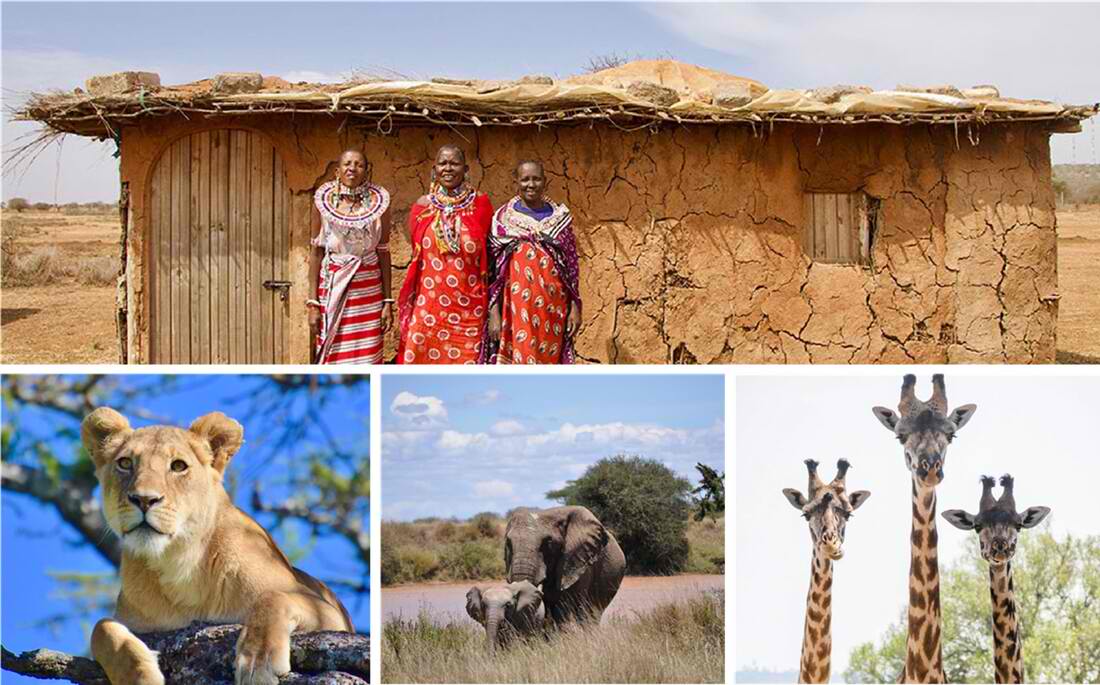

Second, help fill the void left by the collapse of the tourism industry in Africa. Wildlife tourism creates a virtuous circle. The visitor enjoys the safari of a lifetime to the greatest wildlife spectacles on earth, creates jobs and opportunities for communities, and wins a place for wildlife.

For the hundreds of thousands of visitors who‘ve had to cancel or defer safaris, a small portion of the savings made as a conservation contribution will make a world of difference. For others unable to make a wildlife safari, a contribution to community-based conservation helps support the custodians of wildlife.

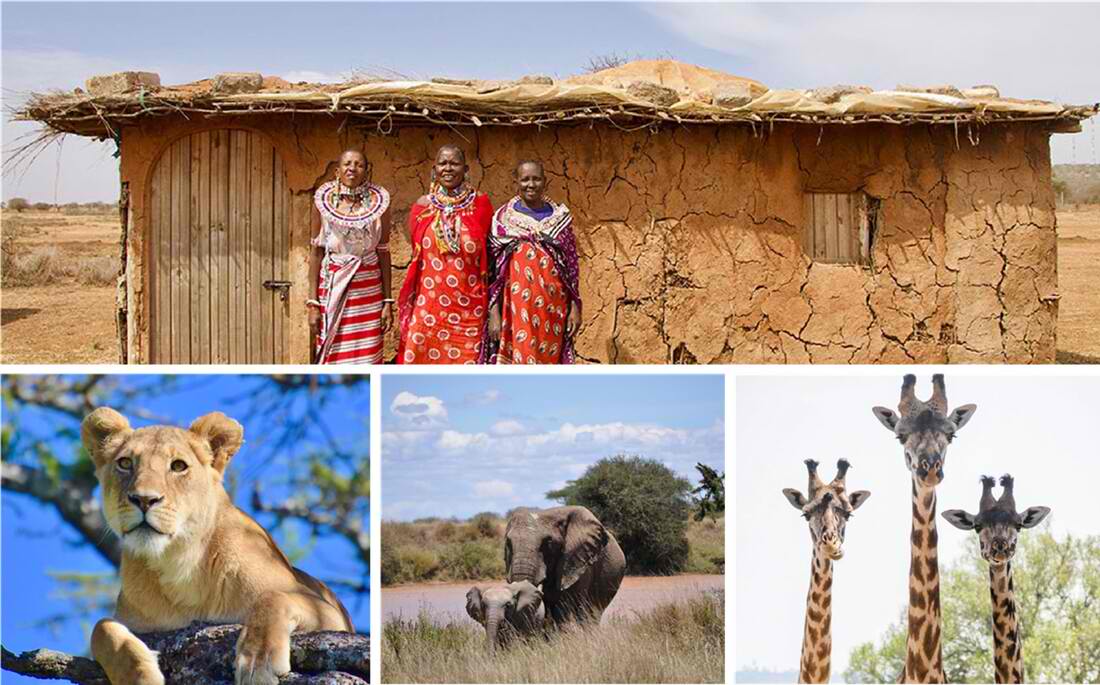

A lion is worth ten times more alive through tourism than supplying claws to the wildlife trade. Stopping the wildlife trade and supporting community programs will help prevent another pandemic and save wildlife.

The pandemic is already disrupting every sector of society, from entertainment and sports to manufacturing and the health and service industries. And the worst is yet to come. Conservationists blame the pandemic on the loss of biodiversity degraded ecosystems and climate change. They have a point. New virulent diseases, along with invasive species and pests, thrive when nature dies.

In the case of the Coronavirus the blame lies squarely on the illegal trade in wildlife species, fueled by globalization. Diseases such as Ebola, Marburg and HIV erupted in small scattered communities in the past but remained localized epidemics. No longer.

In the last few decades, global travel has spawned virulent novel viruses such as SARS, MERS, H1N1 and COVID-19, infecting hundreds of millions around the world in weeks. These new pandemics are a grave threat to every nation, every individual. causing 6 of 10 infectious diseases, 2.5 billion illnesses and 2.7 million deaths each year.

The wildlife trade, worth $23 billion annually, operates largely underground like drug trafficking. And like the ivory wars which slashed elephant numbers across Africa from 1.2 million in 1970 to 450,000 today, the wildlife trade is driven by rising wealth in Asia. Hundreds of species of amphibians, snakes, fish, birds and mammals are butchered for the wildlife trade, among them bats, civets and pangolins suspected of transmitting lethal viruses.

We can’t be sure which species in the wildlife market in Wuhan sparked the COVID-19 pandemic. Regardless, the cramped confined conditions flouting concerns for animal welfare and human health, have unleashed the most devastating pandemic in modern times.

The COVID-19 pandemic has been dubbed the revenge of wildlife. Revenge it isn’t. Coronavirus smites indiscriminately. For every illegal trader infected, hundreds of millions of people are at risk, among them ardent animal lovers, doctors and nurses. Overlooked is the impact of the pandemic on wildlife.

First, lobby your politicians to pressure for the closure of the wildlife trade. A remote shot two years ago, China and other Asian countries have since banned the sale of ivory, showing a total closure is possible. Elephant poaching has declined sharply across Africa since the bans. Now is the moment to press for an end to the animal trade and make the world a safer place.

Second, help fill the void left by the collapse of the tourism industry in Africa. Wildlife tourism creates a virtuous circle. The visitor enjoys the safari of a lifetime to the greatest wildlife spectacles on earth, creates jobs and opportunities for communities, and wins a place for wildlife.

For the hundreds of thousands of visitors who‘ve had to cancel or defer safaris, a small portion of the savings made as a conservation contribution will make a world of difference. For others unable to make a wildlife safari, a contribution to community-based conservation helps support the custodians of wildlife.

A lion is worth ten times more alive through tourism than supplying claws to the wildlife trade. Stopping the wildlife trade and supporting community programs will help prevent another pandemic and save wildlife.

The pandemic is already disrupting every sector of society, from entertainment and sports to manufacturing and the health and service industries. And the worst is yet to come. Conservationists blame the pandemic on the loss of biodiversity degraded ecosystems and climate change. They have a point. New virulent diseases, along with invasive species and pests, thrive when nature dies.

In the case of the Coronavirus the blame lies squarely on the illegal trade in wildlife species, fueled by globalization. Diseases such as Ebola, Marburg and HIV erupted in small scattered communities in the past but remained localized epidemics. No longer.

In the last few decades, global travel has spawned virulent novel viruses such as SARS, MERS, H1N1 and COVID-19, infecting hundreds of millions around the world in weeks. These new pandemics are a grave threat to every nation, every individual. causing 6 of 10 infectious diseases, 2.5 billion illnesses and 2.7 million deaths each year.

The wildlife trade, worth $23 billion annually, operates largely underground like drug trafficking. And like the ivory wars which slashed elephant numbers across Africa from 1.2 million in 1970 to 450,000 today, the wildlife trade is driven by rising wealth in Asia. Hundreds of species of amphibians, snakes, fish, birds and mammals are butchered for the wildlife trade, among them bats, civets and pangolins suspected of transmitting lethal viruses.

We can’t be sure which species in the wildlife market in Wuhan sparked the COVID-19 pandemic. Regardless, the cramped confined conditions flouting concerns for animal welfare and human health, have unleashed the most devastating pandemic in modern times.

The COVID-19 pandemic has been dubbed the revenge of wildlife. Revenge it isn’t. Coronavirus smites indiscriminately. For every illegal trader infected, hundreds of millions of people are at risk, among them ardent animal lovers, doctors and nurses. Overlooked is the impact of the pandemic on wildlife.

First, lobby your politicians to pressure for the closure of the wildlife trade. A remote shot two years ago, China and other Asian countries have since banned the sale of ivory, showing a total closure is possible. Elephant poaching has declined sharply across Africa since the bans. Now is the moment to press for an end to the animal trade and make the world a safer place.

Second, help fill the void left by the collapse of the tourism industry in Africa. Wildlife tourism creates a virtuous circle. The visitor enjoys the safari of a lifetime to the greatest wildlife spectacles on earth, creates jobs and opportunities for communities, and wins a place for wildlife.

For the hundreds of thousands of visitors who‘ve had to cancel or defer safaris, a small portion of the savings made as a conservation contribution will make a world of difference. For others unable to make a wildlife safari, a contribution to community-based conservation helps support the custodians of wildlife.

A lion is worth ten times more alive through tourism than supplying claws to the wildlife trade. Stopping the wildlife trade and supporting community programs will help prevent another pandemic and save wildlife.

The pandemic is already disrupting every sector of society, from entertainment and sports to manufacturing and the health and service industries. And the worst is yet to come. Conservationists blame the pandemic on the loss of biodiversity degraded ecosystems and climate change. They have a point. New virulent diseases, along with invasive species and pests, thrive when nature dies.

In the case of the Coronavirus the blame lies squarely on the illegal trade in wildlife species, fueled by globalization. Diseases such as Ebola, Marburg and HIV erupted in small scattered communities in the past but remained localized epidemics. No longer.

In the last few decades, global travel has spawned virulent novel viruses such as SARS, MERS, H1N1 and COVID-19, infecting hundreds of millions around the world in weeks. These new pandemics are a grave threat to every nation, every individual. causing 6 of 10 infectious diseases, 2.5 billion illnesses and 2.7 million deaths each year.

The wildlife trade, worth $23 billion annually, operates largely underground like drug trafficking. And like the ivory wars which slashed elephant numbers across Africa from 1.2 million in 1970 to 450,000 today, the wildlife trade is driven by rising wealth in Asia. Hundreds of species of amphibians, snakes, fish, birds and mammals are butchered for the wildlife trade, among them bats, civets and pangolins suspected of transmitting lethal viruses.

We can’t be sure which species in the wildlife market in Wuhan sparked the COVID-19 pandemic. Regardless, the cramped confined conditions flouting concerns for animal welfare and human health, have unleashed the most devastating pandemic in modern times.

The COVID-19 pandemic has been dubbed the revenge of wildlife. Revenge it isn’t. Coronavirus smites indiscriminately. For every illegal trader infected, hundreds of millions of people are at risk, among them ardent animal lovers, doctors and nurses. Overlooked is the impact of the pandemic on wildlife.

First, lobby your politicians to pressure for the closure of the wildlife trade. A remote shot two years ago, China and other Asian countries have since banned the sale of ivory, showing a total closure is possible. Elephant poaching has declined sharply across Africa since the bans. Now is the moment to press for an end to the animal trade and make the world a safer place.

Second, help fill the void left by the collapse of the tourism industry in Africa. Wildlife tourism creates a virtuous circle. The visitor enjoys the safari of a lifetime to the greatest wildlife spectacles on earth, creates jobs and opportunities for communities, and wins a place for wildlife.

For the hundreds of thousands of visitors who‘ve had to cancel or defer safaris, a small portion of the savings made as a conservation contribution will make a world of difference. For others unable to make a wildlife safari, a contribution to community-based conservation helps support the custodians of wildlife.

A lion is worth ten times more alive through tourism than supplying claws to the wildlife trade. Stopping the wildlife trade and supporting community programs will help prevent another pandemic and save wildlife.

For over 50 years, we’ve been pioneering conservation work in Amboseli sustained habitats, livelihoods and resilience through collaboration amid environmental changes, protecting biodiversity.

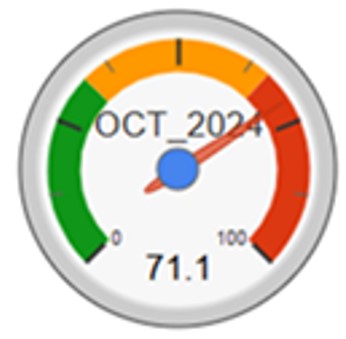

Current grazing pressure percentage.

Amboseli Conservation Program

P.O Box 15289-00509 or 62844-00200

Nairobi, Kenya.

Tel/Fax: +254 20 891360 / 891751

Email: acc@acc.or.ke

Amboseli Conservation Program

P.O Box 15289-00509 or 62844-00200

Nairobi, Kenya.

Tel/Fax: +254 20 891360 / 891751

Email: acc@acc.or.ke